On a popular strategic wargame forum, the user Beginning-Ad980 leaves the following comment: “Soooooo the polish freed Haiti? Whatever ur smoking put it down.” [original spelling] Little do they know that this is actually true. There exists a unique tie between Haiti and Poland that, although admittedly not known to all, is strong in its own way. And all because of the revered Napoleon Bonaparte.

Poles in Haiti: We came to fight… wait! In peace!

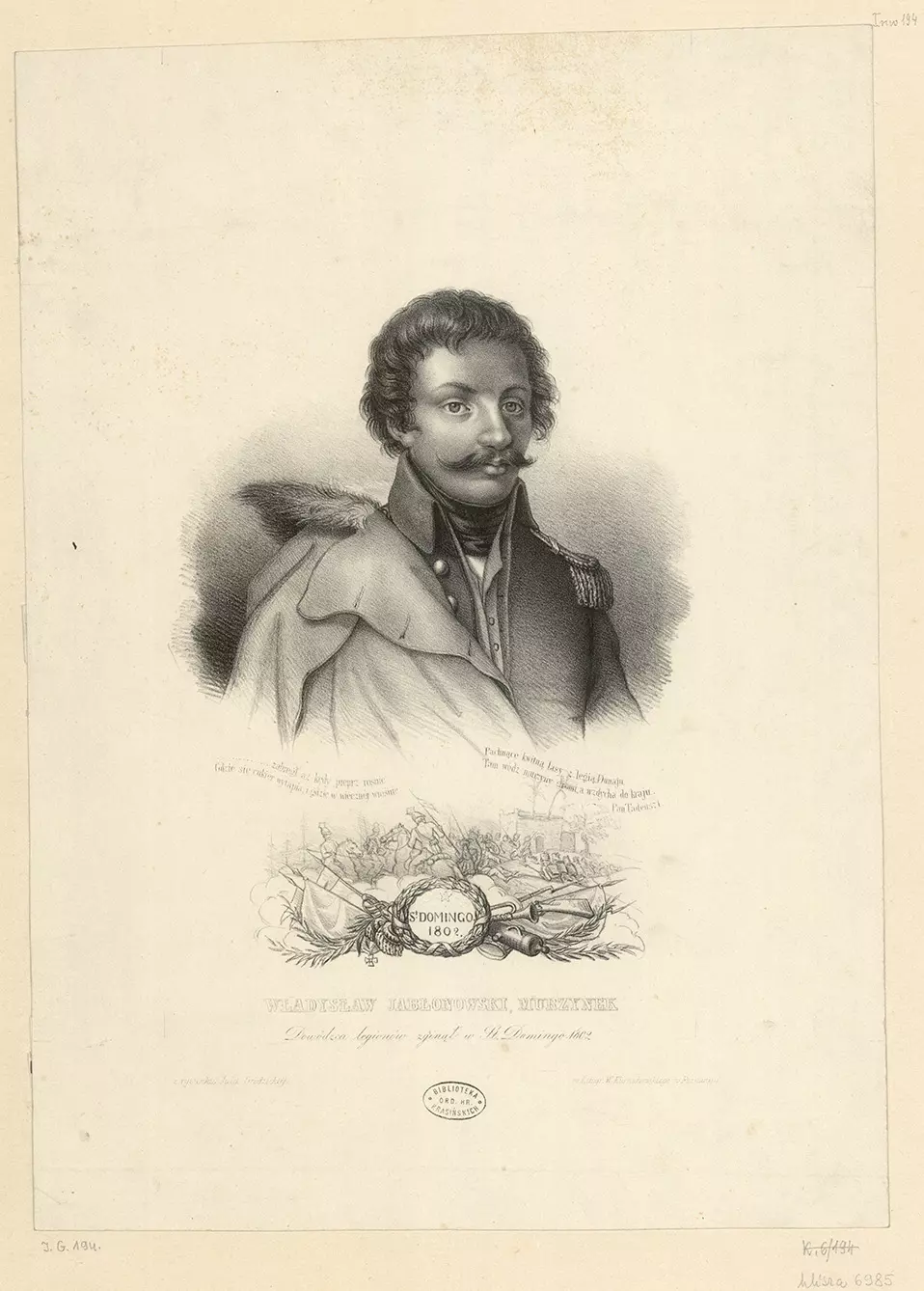

Haiti, formerly known as Santo Domingo, was one of the richest of the French colonies. As fit for the fame of the dark ages of slavery as it can be, the native inhabitants of Haiti were treated cruelly by their French “masters.” After the French revolution, when slavery was supposed to be banned, general Toussaint-Louverture announced the island’s autonomy, declaring himself its life ruler, independent from his French superiors. This did not go down well with Napoleon at all. As he had some units, which became available after signing a peace treaty with Austria and England, he decided to deploy them to suppress the mutiny. It so happened that these units were led by general Władysław Jabłonowski and mainly manned by Polish soldiers. That’s how Poles arrived in Haiti in 1802-1803.

Many of them died due to the Caribbean climate. Those who survived were horrified by the way the French treated native people. Although their allegiance lay with Napoleon and the French, they did not fight eagerly, showing compassion and understanding for the native Haitians. With time, many of them changed sides and started fighting alongside the natives, their hearts coming out to those who yearned for freedom, just like the Polish nation did at the time. Once the native Haitians won, approximately 400 Polish soldiers decided to stay behind and did not return to Europe.

Poles: “The white negroes of Europe”

Their continuing presence on the island was an unprecedented event. The first ruler of the independent Haiti state, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, also known as Jacques I, the Emperor of Haiti, called Poles “the white Negroes of Europe,” which, at that time, was considered a great compliment. And it wasn’t just empty words. In the first Haitian constitution, white people were forbidden to settle in Haiti or own land. With the exception of Poles.

The Emperor also forbade executions of Polish soldiers and granted all of them (including those who remained fighting for the French) Haitian citizenship. He perceived all Poles as a nation devoted to freedom, which had to fight for its own independence more than once during the course of history.

The Polish village of Cazale

The remote village of Cazale became and remained the main center of Polonia in Haiti. The name is said to derive from the Polish surname of Zalewski and replaced the original name of Canton de Plateaux. It isn’t easy to access the village, and its inhabitants live off the land.

Today, the 9th generation of Polish descendants living in Haiti still keeps the memory of the Polish legions alive. Even though the connection is not obvious at first glance, a careful visitor will soon see the heritage of Polish culture. For example, they may notice braids made in Polish [Slavic] style, completely foreign to these lands. They may find inscriptions on old gravestones, reminding them of those long-gone who came to Haiti from faraway lands. And there is, of course, the language – the vessel that carries marks of cultural heritage. Some of this heritage can be seen in surnames – most of which are shortened, French (or rather Creole) versions of originally Polish surnames. Some in names that derive from Polish words.

And then there are expressions completely unique to the place, such as “Là-bas en Pologne” [In Poland…], “M-ap Fe Krakow” [do something Cracovian style – very thoroughly], and “Chajé kou Lapologn” [charge like Polish do – in large numbers, efficiently]. There is also the image of the Virgin Mary of Częstochowa (Poland’s most important sanctuary, famous for its defense during the 17th -century Polish-Sweden war), which is still present today in every Haitian temple, albeit often revered as depicting a goddess of fertility and femininity.

Poland remembers about Poles in Haiti

Even though there is very little preserved original documentation, if any, which would carry more information about the first Poles in Haiti, today’s descendants of the Polish Legions are proud of their heritage and emphasize their not-so-obvious roots. They do not speak Polish and, frankly, very often have little idea of Poland; nevertheless, they do remember. And so does Poland.

Last year in April, the Government Plenipotentiary for Polonia and Poles Abroad, Mr. Jan Dzedziczak, held a videoconference meeting with Haitian Polonia. Among the participants were many descendants of Polish soldiers fighting the French in the 19th century. And if you think this is unusual, wait until you hear about another exceptional undertaking.

In 2015 Joanna Malinowska, assistant professor of the practice in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning, together with C.T. Jasper, managed to realize a project they dreamed up in the early 2000s. They presented Stanisław Moniuszko’s Polish opera “Halka” to the members of the community of Cazale. Despite all odds, the sounds of the Polish masterpiece spread through the Haitian land and reached the ears and hearts of those whose ancestors sprung from what must have seemed to the present-day Cazale natives a foreign culture. Foreign, yet connected. Against all reason.