Before the famous Silly old Bear could get his beloved honey pot in real life, someone had to have worked for it – and worked hard, at that. Poland has a traditional, well-developed culture of forest tree beekeeping that allows bees to lead the way with minimum human interference. Let us tell you a bit more about this fascinating (and sweetly lucrative) trade.

Centuries of tree beekeeping

The first regulations issued for beekeepers in Poland were recorded in the 13th century in Statutes passed by Casimir III the Great. Over the following centuries, beekeepers enjoyed special privileges (they, for example, were exempt from taxes), as their labor was hard, demanding, and extremely dangerous, and its results were to be enjoyed by the community. The beekeeper profession was hereditary – fathers taught their sons as their fathers taught them, and so on. The beekeepers would go for honey hunting around September, which allowed the bees to keep to their natural cycle.

How is it different?

The main difference between forest beekeeping versus the (now) conventional approach is the philosophy behind the trade. Forest beekeepers believe that the bees are perfectly capable of looking after themselves and should not be interrupted. Today’s conventional beekeeper makes the bees settle where they want them to settle in artificial hives, keeping the honey close to home.

Forest beekeepers leave their bees to their own devices. They cautiously and hardly tend to them, ensuring they are safe and have the best conditions to thrive. They are completely committed to the natural cycle and nature’s ways. Their role is also different. While a conventional beekeeper acts like a bee manager, a traditional beekeeper must ensure the bees will want to stay in their wild beehive. They carefully recreate the natural hollows of the trees and wait to see if a swarm feels at home enough to start a colony inside. It’s not all entirely up to chance though – there are special ways to encourage bees to turn an artificial natural-like hive into a home that involves herbs, honey, and propolis, among others. There is also an obvious difference in the location of these hives.

How do you keep bees in the forest

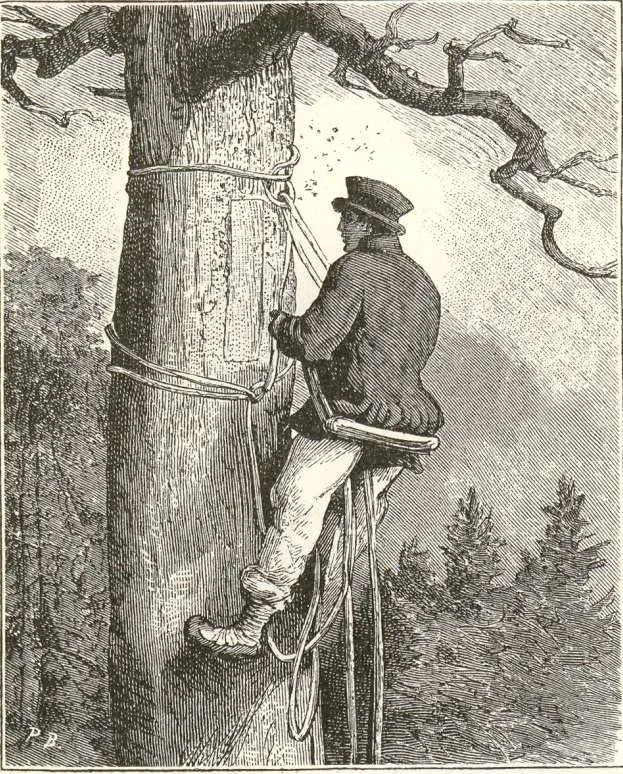

While conventional beekeepers bring the bees closer to the ground in small, ground beehives, traditional beekeepers know that the insects are happiest high up the tree trunks where they would naturally start their colonies. And so, the forest beekeepers make their wild beehives either directly in the trunks of forest trees, some 3-4 meters above the ground – or inside logs installed high up in the trees.

Wild beehives are handmade holes carefully hollowed out in the trunks and logs. “The walls need to be about 8 centimeters thick. The entrance is about 10-11 centimeters by 90 centimeters. The depth varies from 30 to 40 centimeters. But it all really depends on the size of the tree – it has to be properly adjusted to the trunk,” Piotr Piłasiewicz, a young beekeeper, mentions in a short documentary from 2014, where he shared his passion for forest beekeeping.

Another culture

What is striking is the abundance of vocabulary specific to the trade of forest beekeeping and the beekeeping profession. Every element, tool, and activity seems to have a unique and original name, which may vary from region to region. However, one common word that would be important to mention is the ciosno.

What the heck is a ciosno? Well, have you ever wondered how on earth the beekeepers would recognize their hives from the hives of other beekeepers? Disappointingly for some, they did not have supernatural memories and topography senses – instead, they would mark the trees with their trademark, to put it in contemporary terms, which was known as ciosno (in Polish, ciosać means to “carve.” A literal translation of ciosno is, therefore, a carving.) And what if you were naughty and stole some honey from the competition? Well, if you were caught, the punishment involved being hanged by the feet by the entrance to the beehive (and we should hope you were allowed to keep on your garments – we have not found relevant sources to confirm that, though!)

Is it significant to the environment?

YES! Supporting the bees and other pollinating insects is a major concern for today’s environmentalists. Polish Forests run a program known as “The Bees’ Return to the Forests.” Its significance is complex. Firstly, it is to promote the traditional forest beekeeping culture that, once great and important, went extinct in Poland in the 19th century. Between the years of 2006-2008, it was reintroduced and, since then, has been winning over the interest of hobbyists and professionals alike. Contemporary forest beekeepers want to cultivate the tradition and promote the centuries of knowledge gathered by previous generations of beekeepers. They also want to help the bees, sometimes supporting particular breeds that are currently endangered the most.

Treasure of humanity

In 2020, the uniqueness of the beekeeping culture in Poland was added to the Intangible Cultural Heritage list, testifying to its importance and significance to the Polish people and humanity. Now, in 2023, nearly twenty years after the revival of forest beekeeping in Poland, the prices of traditionally obtained, 100% natural and organic honey from Polish forests are yet another reminder of why it was referred to as “liquid gold.” It is, however, the reflection of the hours of labor, effort, and generosity of the bees, who graciously allow humans to share in the fruits of the hard work they undertake for the survival of their species.