The magazine’s history, possibly unlike any other magazine in the world, is curious at every stage. In fact, the only real fiasco in the decades of its history was the effort to “normalize” Przekrój and adjust it to capitalist market rules in the 1990s.

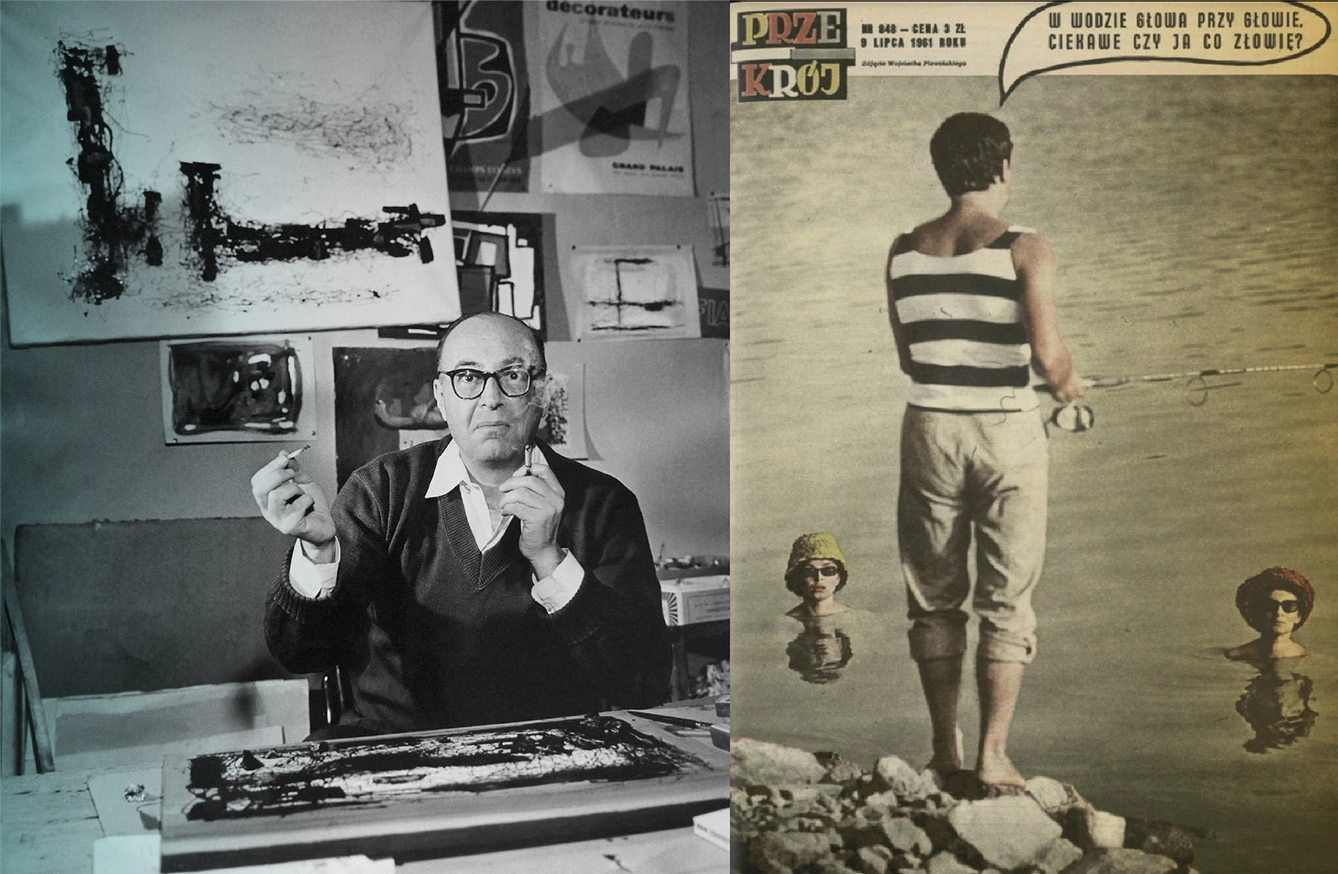

Przekrój’s Painter-in-chief

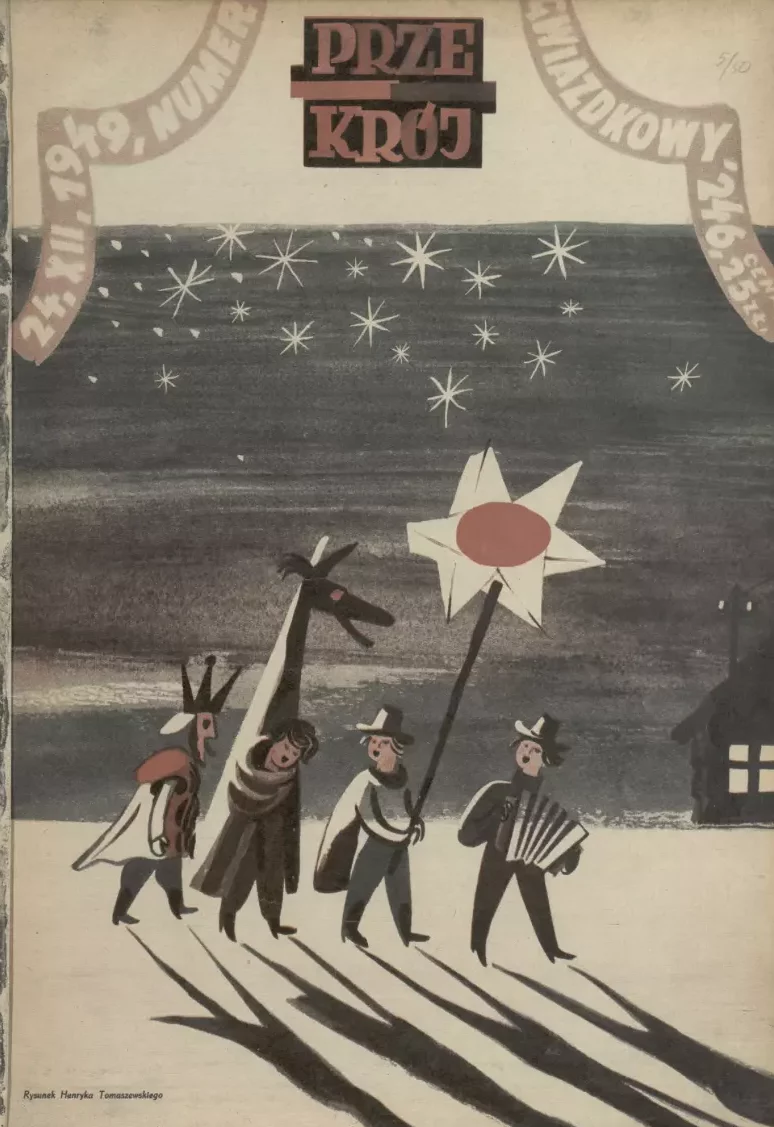

In 1945, Marian Eile, a painter by training, was approached by a political friend on the street in Łódź, Poland, and offered the position of editor-in-chief for a newly created weekly. He agreed and was promptly flown to Cracow, where the publishing headquarters were being established – by cropduster. This sole image – a painter-turned-magazine editor overnight ferried across the country by cropduster – should be enough to paint the picture.

But in Poland in 1945, largely in ruins and depopulated by war, just the act of creating a magazine was curious enough. Cracow was chosen as the location for its headquarters as it was one of the only cities that hadn’t been entirely decimated in the war (as Warsaw was). It helped that its national belonging was not in dispute (as was the case of cities in the East, as well as former-German cities in the Northwest).

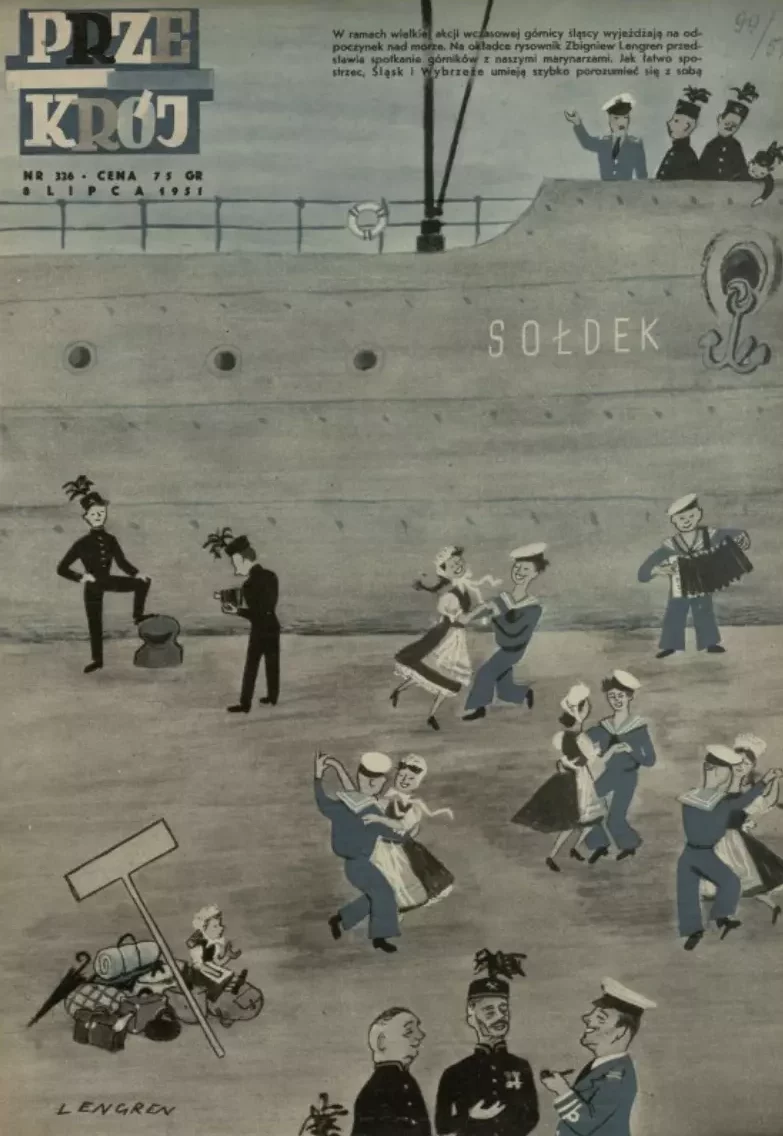

Soon, Marian Eile was joined by another painter named Janina Ipohorska, who came on board as second-in-command. And so, a weekly run by two painters started publishing whatever its editors felt like. Its graphic design was off-grid, both figuratively and literally. Drawings were inserted into the text at full liberty, typeface changed from page to page, and long-reads disappeared suddenly only to reappear half an issue later.

The conventional order Przekrój lacked in graphic design… well, it also lacked when it came to content. During Stalinism, when every major newspaper and magazine in the country was literally being sent political press releases, Przekrój took the liberty to broaden the magazine’s scope beyond limits. They even refused to publish Stalin’s official obituary in 1953, a bold political move not without repercussions, as hardcore Stalinism ended only three years later.

Not-so-socialist lifestyle

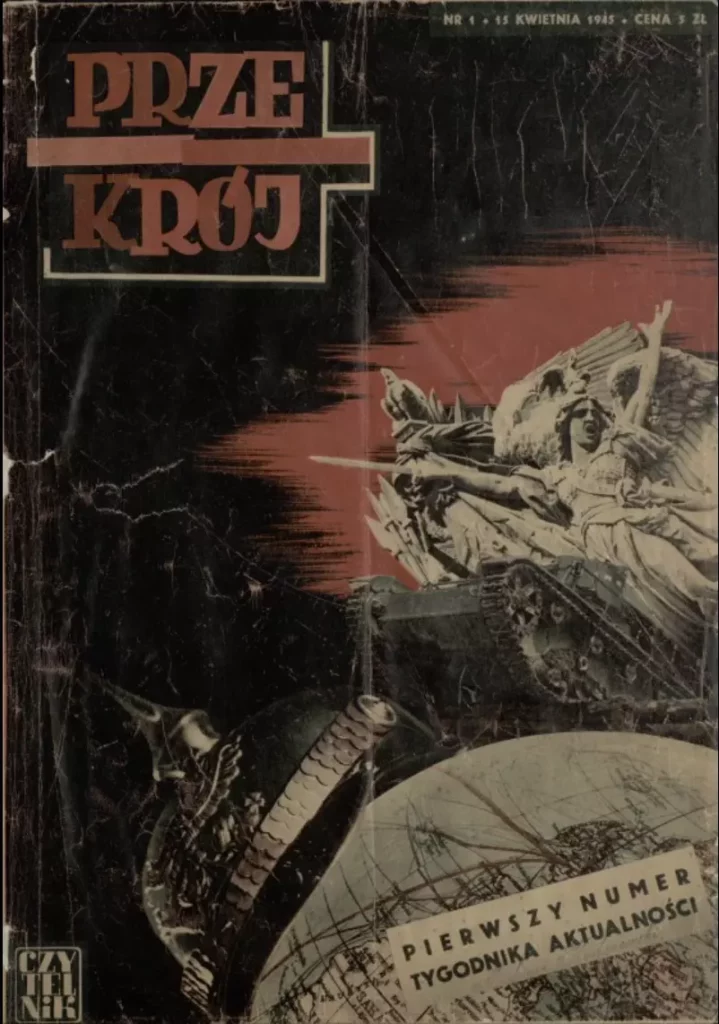

Beyond that, its provocative role in forming a new, not-so-socialist man is hard not to appreciate. Not only did it publish contemporary literature and notes on art trends in the West. It also took up what was later called by scholar Justyna Jaworska “a civilizing mission.”

The mission was, in a way, a precursor to the TV makeover format of today to turn people from lower to upper class overnight, just without the before-and-afters. They fought against the (perhaps more patronizing than chivalrous) act of hand-kissing women, which they called “kiss-nonsense”. They engaged in a decades-long crusade against the alcoholism-inducing ways of bingeing vodka, advising Poles to turn to (socialist) Hungarian wine and (socialist) Bulgarian cognac instead.

But the advice and encouragement didn’t stop there. They civilized house parties with pieces featuring advice on table decor, different party formats, elements of politeness, and, last but not least, recipes. The latter was important as Poland was a land of scarcity in the 1940s and 50s, meaning throwing any formal dinner together was a struggle. The same goes for fashion – Przekrój played on the idea of a DIY magazine, not by proposing new creations but by making use of the bland, shapeless, boring pieces of clothes available in stores.

With all these functions, it’s astonishing that it lasted throughout socialist Poland (and beyond). After two decades of serving his people, Marian Eile stepped down as editor-in-chief in 1969. However, this mission continued into the seventies and even eighties. After political and economic transformation, attempts were made in the 1990s to reformat Przekrój as a “regular” socio-political magazine, but it failed to serve such a function.

It is currently published as a quarterly, largely benefiting from its original design, ideas, and archives. Its social and cultural scope is a tribute to its lifelong tradition. As such, it is one of the most thriving ideas in the history of Polish publishing.