And don’t worry if you have no clue who he was. We don’t blame you! Sadly, this great 17th-century explorer (and a Jesuit) is largely unknown. So let’s change that!

Here is a brief story of Europe’s pioneering sinologist, who was one of the first to record the culture and geography of China and the first to record the methods used in Chinese Medicine, even though a Dutch doctor temporarily stole the credits for the work.

Hungarian origins

The Polish line of his family started with his grandfather (György Boim), who settled in Polish lands and married a local woman. His father, Paweł, was a physician to Polish King Sigismund III Vasa. Unsurprisingly enough, Paweł took care of his children’s education, and his son, Michał, joined the Jesuit Order when he was about 19. Although being 19 in the 17th century was practically full-blown adulthood, it is still interesting to note that it is said Michał joined the Order fulfilling the promise given to God when he recovered from a serious illness at the age of 14.

The Jesuit Order is the same one which can be credited for educating masses of young people, as one of the Order’s missions was to spread knowledge. Therefore, Michał’s brilliant mind was in good hands. For ten years, he was educated and prepared for his mission to the Far East. Finally, in 1643, he set off for China.

Early years in China

After a long route that took him from Portugal, around Africa, and Portuguese-controlled Goa in India, Michał arrived in Macau, China. It was there in one of his Order’s schools that he began to study Chinese, eventually making it to the Hainan province (the smallest Chinese province comprised of small islands). He was the first European to describe thoroughly the lands he served in.

As the times were turbulent, marked with the struggle for ultimate power between the two dynasties – currently residing at the time in the Ming dynasty and the aspiring Quing dynasty – Hainan fell under the control of the new powers, and so Michał left the Island for Tonkin (today’s Vietnam). He stayed there for two years and, in 1649, was delegated to the court of the Yongli Emperor, who was desperately trying to keep his dynasty at the helm of the country. As the Emperor and his entire family converted to Christianity, he made Michał his (last) ambassador to the Holy See and other European countries. He asked for support in his struggle at trying to repel the Manchurian aggressors. This was the beginning of a long and final journey for Boym.

Years-long adventures and what came out of them

He carried letters from the Emperor to important Western figures, such as the Pope, the Portuguese King, and the Dodge of Venice, to name a few. It is impossible to write in detail about all the adventures and places Michał visited. But not to disappoint you thoroughly, let us tell you about the tangible monument to his endeavors.

Namely, the priceless manuscripts. Boym was a keen observer both of nature and people. We are talking about the 17th century, yet Boym had this incredible gift to look at people without prejudice and in the spirit of equality. He never lost his identity or faith, but when in Rome, he did as the Romans did – dressed, talked, and lived like them.

And just how open-minded Michał Boym was can be seen in his research into the Bantu Kaffirs peoples tribe (150 years before the credited John Barrow). They were known for their cannibalism, yet Boym talked to them about their customs, and there even is a record of his conversation with a man who consumed a human head! This says a lot about Boym’s attitude and lack of reservations when studying foreign cultures. His observations can be studied in his manuscript entitled Cafraria, a P.M. Boym Polono Missa Mozambico 1644 Januario 11.

Cartographer

He also made the first (never published) comprehensive map of China, for the first time correcting the geography of many cities, locations of which were somewhat displaced in the understanding of people living in the Old Continent. He also included the location of strategic mines and was the first scientist to correctly identify the Korean Peninsula as a peninsula, not an island as it was believed to be at that time. His map was revolutionary as, after Marco Polo’s voyage, all that was known was the shoreline of China – not the inward land. The Vatican Library still holds his manuscripts under the name of Magni Catay and Mappa Imperii Sinarum, and it is available online.

A botanist and something extra

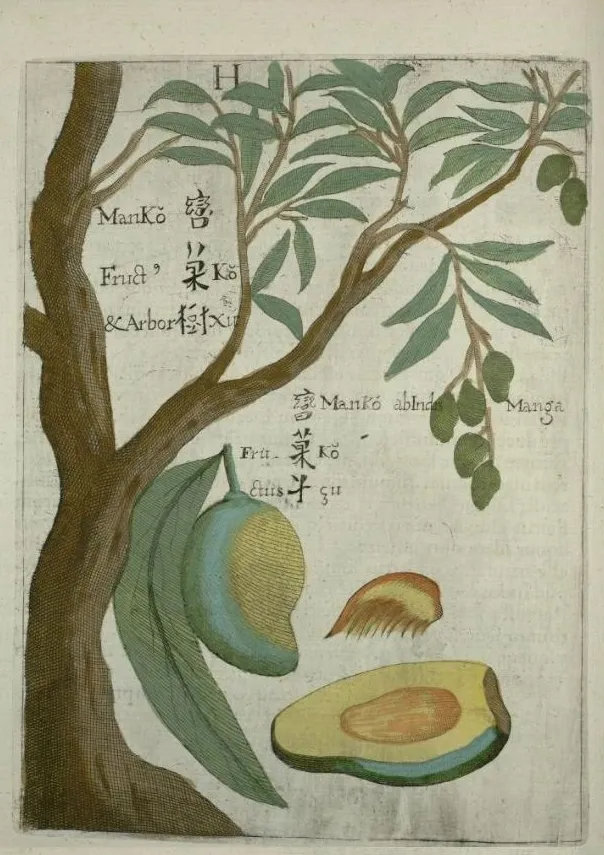

Another great manuscript, Flora Sinensis, is the first comprehensive description of China’s flora (fun fact: Boym was the first person to use the term’ flora’ to describe vegetation growing in a place). Beautiful pictures of plants present in China, their Chinese names, as well as medicinal properties are enough to find this work exceptional, but it was more than that. Flora Sinensis also includes descriptions of Chinese animals and some historical facts about the country. It is considered to be the greatest of his preserved works.

Manuscripts worthy of a sin

Now to the history of intellectual property theft. When Boym was trying to return to China with the word from the Pope and other leaders directed at the Emperor, he knew his mission was extremely dangerous and might perish. He, therefore, gave the manuscript of his Medicus Sinicus to a fellow Jesuit, asking him to carry it safely to Europe. It included an explanation of the diagnosis of illnesses via examination of pulse, the yin-yang principle, and acupuncture. Anyway, his Jesuit friend did succeed, and the work was published in 1682 in Frankfurt under the name of Andreas Clayer, who decided to steal Boym’s work.

Thankfully, the plagiarism was finally discovered, and the authorship went duly to the real author. As you can see – Boym did not waste time during his travels and left many works describing life on the lands he visited (some of them did not survive to our times).

Unknown place of final rest

Returning to Michał Boym’s main mission – he was determined to keep his word given to Emperor Yonlgli. However, the changing situations in the lands prevented him from ever reaching the Emperor, whose dynasty finally succumbed to aggressors. Boym died en route from exhaustion on 22 June 1659 in the presence of his faithful friend and companion, Andreas Zheng. He was buried by him somewhere along the Royal Tract from Hanoi towards Nanning in the Guangxi province.

And although the exact location of his grave is unknown, his legacy lives on. He is remembered in Chinese history and lives on in the memory of those fascinated by China. As one of the founders, you may say, of sinology, Boym is a character that deserves recognition. His life can still serve as an inspiration to future generations.