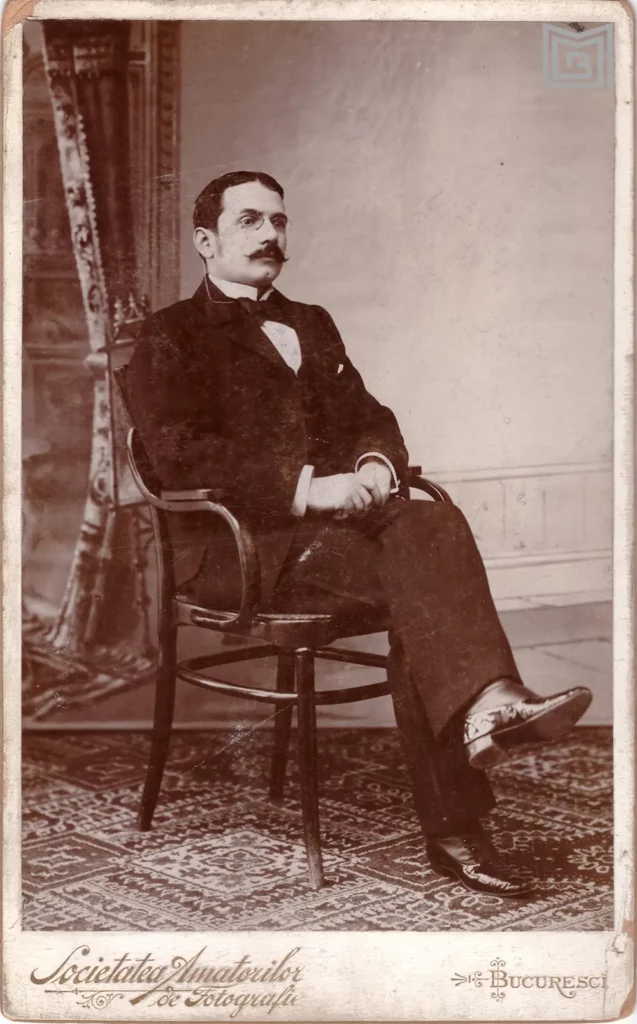

Chances are that, more often than not, whenever we hear about a distinguished and famed scientist, it is often the case of a child prodigy, easily recognizable from a young age. Their interest, passions, or maybe family record set them apart, and one can quickly point out the direction in which their life would evolve. However, there are some special cases where a sudden change can forever impact the life o a person and bring to light the genius within. Victor Babeș was such a case. A scientist whose inclination and talent towards medicine did not spark by itself, but it was the result of a sadly traumatic event.

Ever since he was a child, Victor was attracted to the arts. Be it poetry, music, literature, or drama – young Victor found great passion in creative works, so much so that he began pursuing this path and enrolled in Performing Arts in Budapest. Not long after that, Victor was to face one of the most terrible moments of his life, one that would alter the course of his life. His beloved sister, Alma, died of tuberculosis. Her death was the catalyst in Victor’s desire to stop being a mere bystander to the tragedy such diseases bring upon humans.

Victor Babeș: from poetry to bacteriology

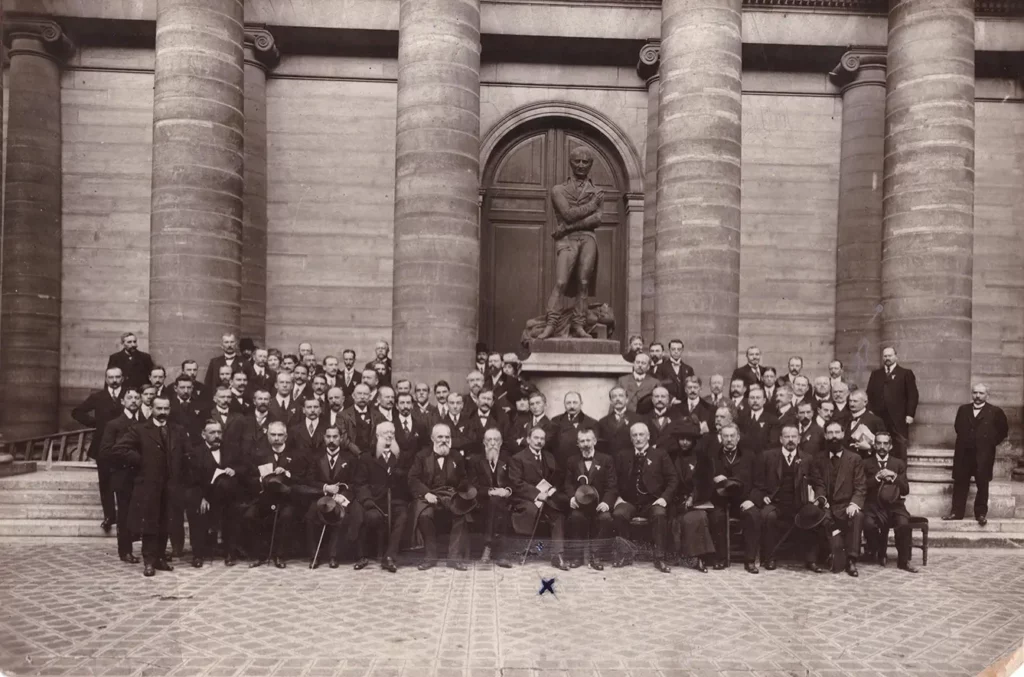

More determined than ever, with a new goal in mind, Victor Babeș began studying Medicine in Budapest and Vienna and attended scholarship Universities in Paris and Berlin. He would then work side by side with some of the world’s most acclaimed scientists Cornil and Louis Pasteur, with whom he would revolutionize the field.

Victor Babeș wrote, together with Cornil, the world’s first-ever treatise on bacteriology. After Louis Pasteur, he would be called the world’s second most prominent expert in rabies. He discovered Babesia – microscopic organisms and parasites carried by various ticks, that affect the red blood cells. Many considered the Romanian scientist worthy of a Nobel Prize, and he would have won it had he remained outside the Romanian borders.

But Babeș was more than a bright scientist – he was a tender soul. His passion exceeded medicine and reached far grounds, like the ones of patriotism. When he was called home, he returned to Romania, leaving behind the prestigious life he could have had. His contributions to the field of medicine within the Romanian borders were immediate. He inaugurated the Institute of Bacteriology and Pathology, which still today bears his name.

The human survival instinct

He opened the Anatomic Society in Bucharest, and World’s third anti-rabies facility was opened in the Capital. As the precursor of modern immunology, he was the first to introduce the concept of antibiosis worldwide – anticipating the emergence of antibiotics in the mid-20th century.

And because it all started due to a tragic loss, Babeș dedicated his life to studying and treating rabies, tuberculosis, and leprosy, and treating the Romanian Army during the Second Balkan War. He manifested great interest in prophylactic medicine (medical and sanitary measures imposed to prevent the occurrence and spread of diseases). The main beneficiary of his work was not the field of medicine but the individual – the human and its survival.

Today, Romania’s most prestigious institutions, such as the Babeș-Bolyai University, the Babeș National Institute of Pathology, and numerous other institutes, schools, and hospitals carry the name of the scientist.