Although, undoubtedly, this fact itself could serve as an achievement worthy enough to go down in history, Wacław Seweryn Rzewuski did much more than that. And there are grounds to suspect many of his achievements were to restore his family’s good name that his father tarnished. Let us tell you about a true Polish King of the Orient.

Treason and a new life

The end of the 18th century was a turbulent time for Poland. The weakened country became an object of interest to neighboring powers who wanted to divide it between them. They succeeded, and Poland was divided into three steps starting in 1772 – the process is known as the partitions. It would not have been possible if a certain group of nobles was not pushing for such an unorthodox solution, seeing an opportunity to gain influence, riches, and what might not.

And so Poland, the first European country with a constitution (1791), ceased to formally exist in 1795. And Sewryn Rzewuski, Wacław’s dad, belonged to the ‘Targowica Team’ – the treacherous group leading to such a sad end of a great Kingdom. Unsurprisingly, Seweryn was sentenced to death and held in eternal disgrace; he lost all his offices and honors, and all his assets and properties were confiscated. The sentence was carried out using a likeness of the once respected hetman (commander-in-chief). He managed to escape to Vienna in 1794, taking Wacław and the rest of his family with him.

Early interest in the unknown

Wacław manifested great interest in the Oirient from an early age. One can speculate he was under the influence of his uncle, another great Polish early expert on the Orient, Jan Potocki. In Vienna, he studied Arabic and Turkish. His uncle also made it possible for him to meet great Vienesee experts on Orient – Julius von Klaprotha and Josef Hammer von Purgstalla.

He also got very involved with a periodical, Mines of Orient, which he not only financially supported but also promoted and corresponded with many academic societies. In 1810 he became a member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities, the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, as well as the Warsaw Society of Friends of Learning (1815). After leaving the military and finally completely growing apart from his spouse, to whom he was unhappily married, he decided to follow the calling and head to the mysterious East.

Sure, buy me a horse in Arabia!

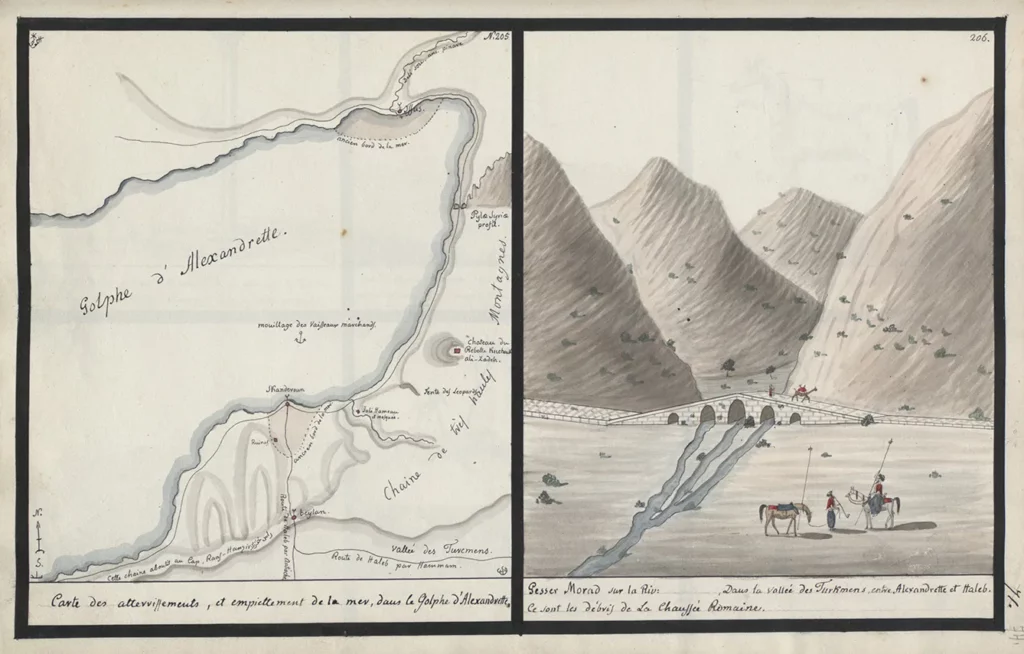

The plan was simple. He ‘just’ needed the right sponsor. The force was strong with this one, you may say, as without hesitation, he went as high up as he could – straight to the tzar, Alexander I of Russia (who at the time also ruled over what was part of Poland), and his sister. He planted the seed and patiently waited for two whole years. In 1817 he was finally able to set out to the unknown lands he’s been dreaming of all his life. He traveled the lands of the Arabian Peninsula and today’s Turkey and Syria (mind you – at that time, the Turkish Empire ruled over most of those lands).

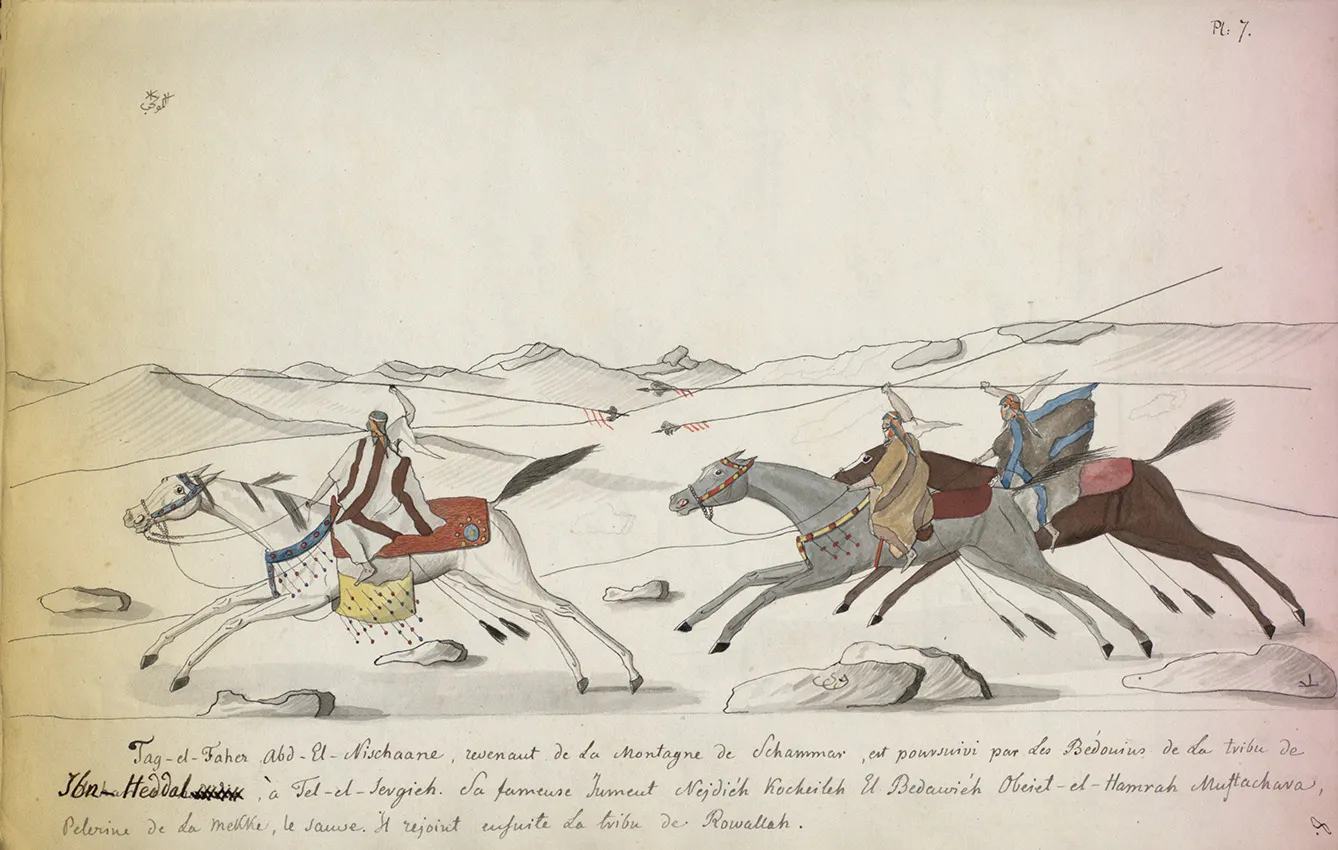

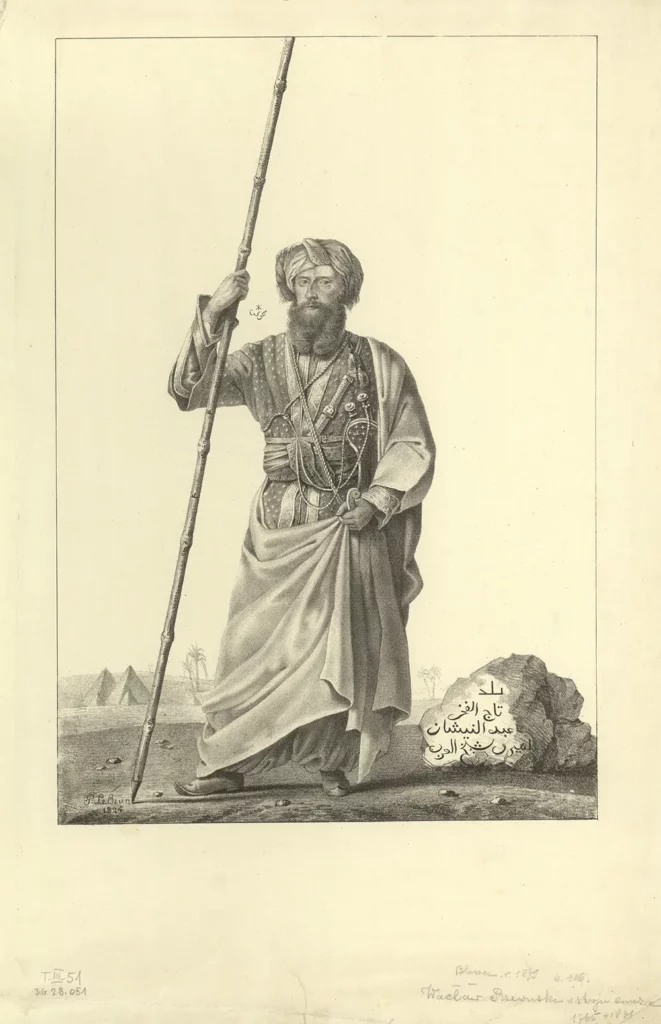

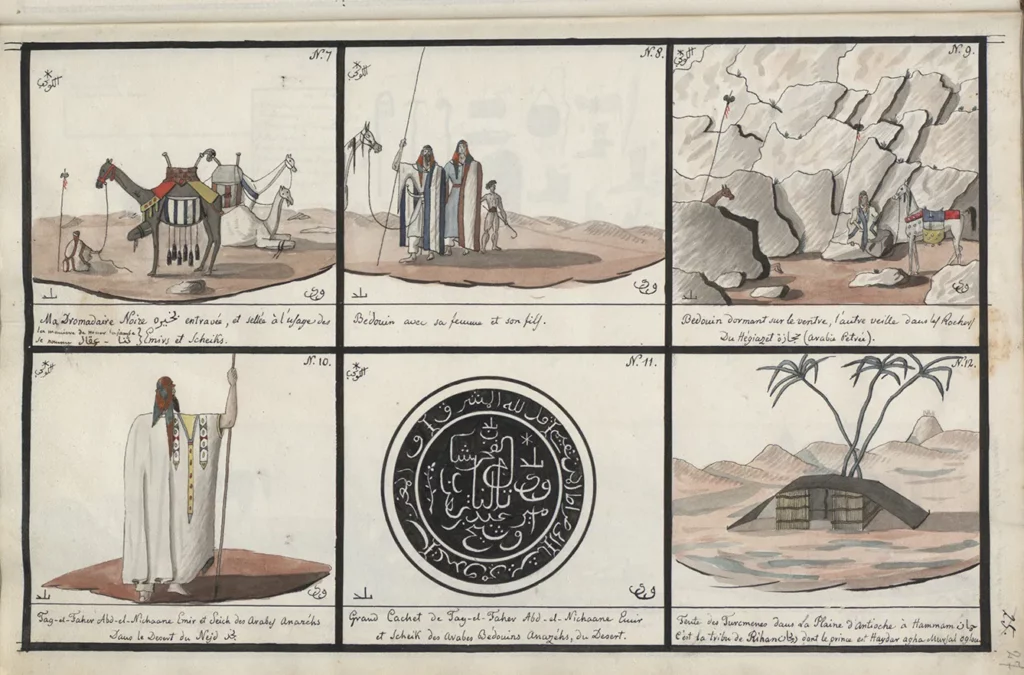

He was fascinated with people’s way of life, especially the Bedouins. He completely immersed himself in their culture. And it was appreciated by the locals too! Thirteen Bedouin tribes accepted him as their own, and he was granted the title of an Emir. They called him Ab-al-Nishan (The Servant of the Sign) and Taj al-Fahr (The Crown of Glory).

Sometimes you just don’t return

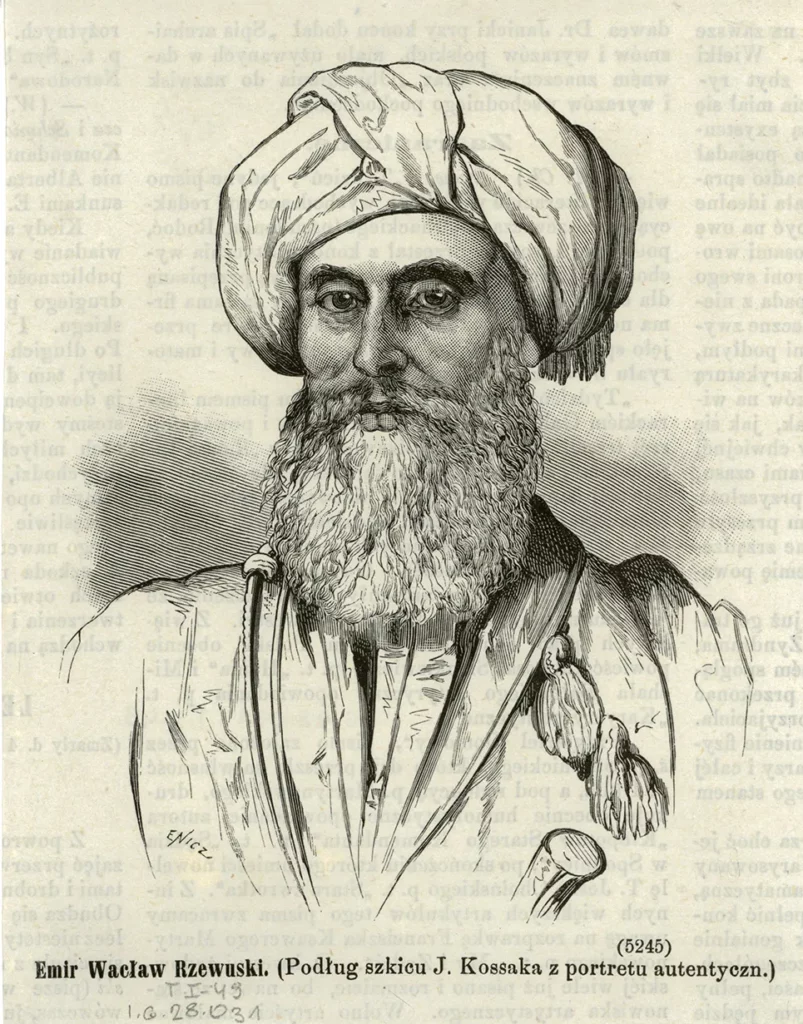

Rzewuski returned to his house in Poland in 1820. But he was not the same man. His journey was life-changing. He started dressing differently, kept to habits acquired during his time in the desert, and liked to hang around with the Cossacks, whose lifestyle reminded him most of the freedom he found during his travels. The Cossacks nicknamed him the One with the Golden Beard.

The revamped image of Wacław became the source of inspiration for great Polish Romantic poets such as Mickiewicz and Słowacki (and the former is said to have met Rzewuski in person while in Crimea). As the Polish-male version of Sheherezade, Wacław inspired the imagination of everyone who listened to his stories of ruins uncovered, fights fought, songs sung about him by the local Arabs, and of princesses he kidnapped (we take it that for a good cause).

Ok, but what happened to the horses?

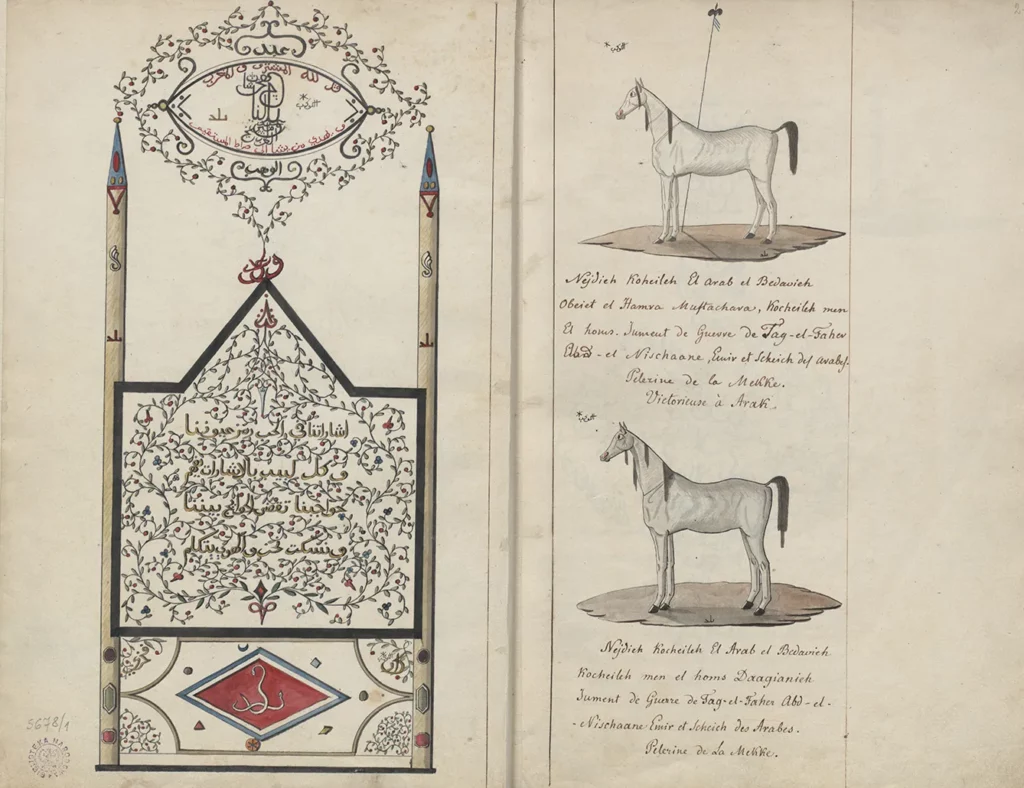

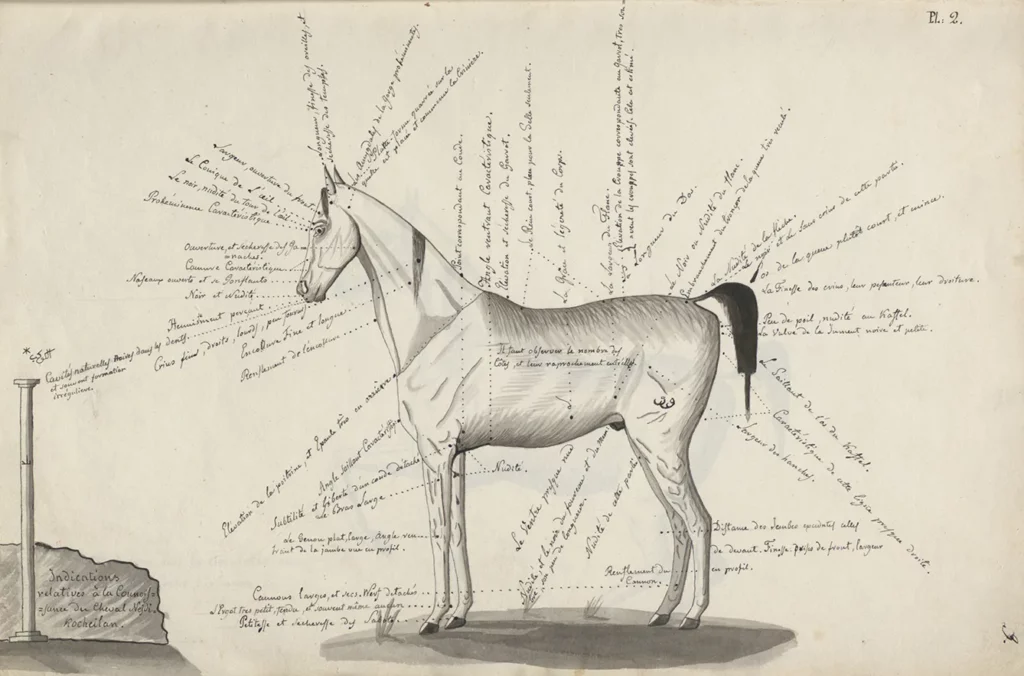

Oh, the horses were just fine. Rzewuski did keep his side of the deal and purchased herds of pure-blooded Arabian horses he shipped back to the tzar. But that’s not the most important thing. Most importantly, the horses inspired him to write a three-volume manuscript entitled Concerning the Horses of the Orient and Those Originating from Oriental Breeds. Let the title not fool you. His work is unique on a global scale.

It is a detailed account of his trip, with 500 pages, including about 400 wonderful illustrations not only of the horses (whose breeds are indeed specifically described) but also of maps and the Bedouins, their customs, and culture. Rzewuski immortalized Bedouin poetry and songs (inclusive of notated melodies), and clothing. He described the lands he traveled and made notes of routes, climate, weather – you name it, he made a note of it. After over 200 years since his journey, the book became an invaluable source of knowledge in many fields. Carefully reprinted by the Polish National Library, it is possible to be purchased today (translated from the original French into Polish and English).

Reclaimed honor

And just when you may think that surely no one held a grudge against the Rzewuski family after Wacław’s extraordinary achievements, think again. I mean, the grudge was gone, but not just because Rzewuski loved the Orient. After returning to Poland, he joined the conspiracy leading to the November Uprising of 1830. He joined the army and died in battle on May 14, 1831. He was that kind of a man – with the Polish heart burning like the Arabian sun.