One thing you can say about Estonians is they sure know how to chill. Being the northernmost country of the Three Seas region has some serious benefits, though a tropical climate is certainly not one of them. But think of midnight sun, snow baths after sauna, driving to the islands on the sea surface and, wait for it, fighting enemies from the east, the ice-skating revue style.

Lake Peipus: Between Papacy and Novgorod

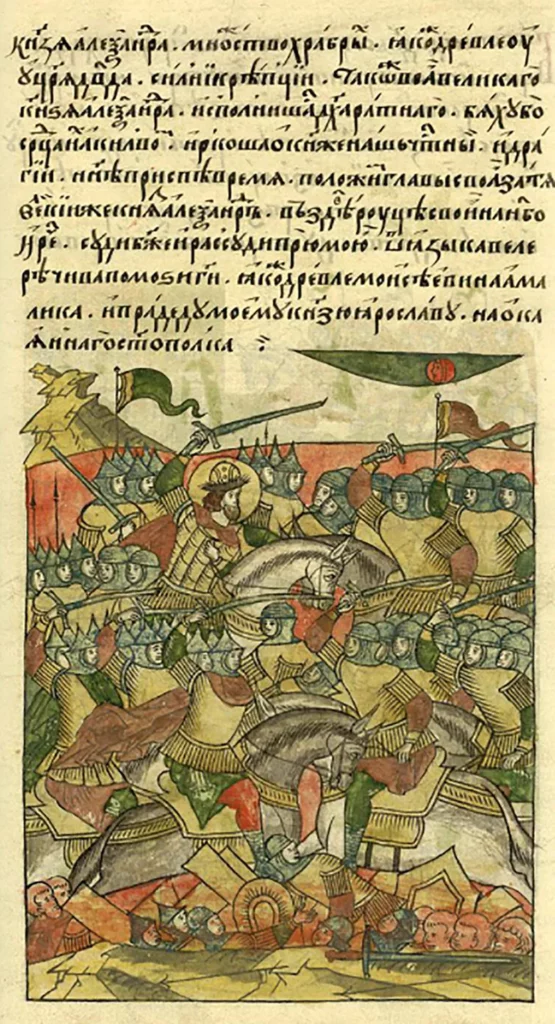

Yes, in the 13th century, the forces of the Livonian Order, the German knightly order that was the precursor to today’s Estonia, allied with the Bishopric of Dorpat (currently the Estonian city of Tartu) to fight against the movie-famous Alexander Nevsky of the Republic of Novgorod.

The late Middle Ages was a time of political-military turmoil on the eastern frontier of Central Europe. With Baltic tribes still pagan, Catholic forces, represented by the Teutonic Knights and their spin-offs (Livonian Knights being the most notable of the latter), organized conquests based on the idea of crusades. With the blessing of the Papacy, whatever they conquered was tuned into their own dominions, forming countries ruled by warrior monks.

On the other side of the frontier, early-stage countries adopted the Eastern Orthodox Christian denomination exported from the Roman Empire in Constantinople. Basing their existence partially on conquest, they moved further west. The struggle for both sides was multifold: establishing the proper borders of the countries, as expanded as possible, of course, to pillage and export the religion.

The strategic goal of Eastern tribes and societies was to stop the expansion of Western knightly orders to the east – and the struggle was real, as in the 1240s that interest us here, the Teutonic Knights and their allies from Estonia attacked the Novgorod Republic and occupied Pskov.

Battle on the Ice

The country’s capital, Novgorod, was close when the young Prince Alexander Nevski changed the course of the war, reconquering Pskov and advancing west. Nevski’s forces were defeated near Tartu and retreated, forcing Western combatants to follow them to the narrow strait between Lake Peipus and Lake Pskovskoye, a double-lake natural barrier of strategic importance.

But Novgorod strategically retreated even more. The Western knights, typically heavier armed than their Eastern counterparts, were confident enough to pursue Alexander Nevski’s men crossing the frozen lake. This is where the clash began.

And yes, it was a literal Battle on Ice. Crusaders attacked across the lake but were stopped before their charge got to the other side. Novgorod engaged them with Russian allied forces that exhausted knights, including mounted soldiers, having to beat not only their opponents but also the slippery floor of their battlefield. After some two hours, when the Western knights were already unfit to prolong the battle, Nevski commanded his cavalry to attack, causing panic among Catholic ranks.

There is even a myth, now debunked by historians, of the ice cracking under soldiers’ feet and the knights drowning in Lake Peipus. The image was proliferated by Sergei Eisenstein’s 1938 film Alexander Nevski, a great modernist movie and a Soviet propaganda piece exploring the motif of a clever and fierce Russian leader defeating Germans.

The battle was not exactly epic in terms of numbers. Some few thousand people engaged in the Battle on the Ice altogether, with Livonian chronicles claiming twenty-some killed and captured and Novgorod ones bragging about “countless” Estonians and hundreds of Germans killed.

But the hostage of the war was the cultural influence. After the defeat of the Livonian Order in the Estonian-Russian frontier, the border of Catholic and Orthodox denominations was set. Alexander Nevski remains the saint of the Russian Orthodox Church and, by the decision of Catherine the Great became the patron of the Russian military order.

As history is being constantly revised, the Battle on Ice on Lake Peipus remains symbolic, and its unusual setting still is an inspiration – after all, it all sounds too fantasy-like to be true.