Way up in the north, where winters drown the land in darkness and summers compensate the people bringing them the gift of white nights, lies a country the spirit of which was tested by many centuries. However, the nation prevailed and secured the existence of one of the least-known states of the Three Seas Initiative. It’s time you should get to know the history of Estonia.

Probably the oldest European locals

Every story has its beginning. The beginning of the story of Estonia is, indeed, an early one. In fact, some scientists believe Estonians are one of the oldest settlers who came to live in Europe. Besides genetic testing, the clue which made them arrive at such a conclusion can be found in the Estonian language. It belongs to the Uralic family and its Finno-Ugric group and is more closely related to Hungarian than to any immediately neighboring 3Seas Countries. The earliest human settlement, on the other hand, is connected to the Kunda culture and dates back to about 9000 BC, which sheds additional light on the origins of the ancestors of Estonians.

All this means that the earliest settlers spoke some form of proto-Uralic language and were present in the area virtually immediately after the last Ice Age. What happened later, sometime around 4200 BC, namely the arrival of the Comb Ceramic Culture, was likely a result of improving living conditions in the area, as the climate was slowly warming. It is also worth noting that Estonia was possibly one of the earliest named domains of Europe.

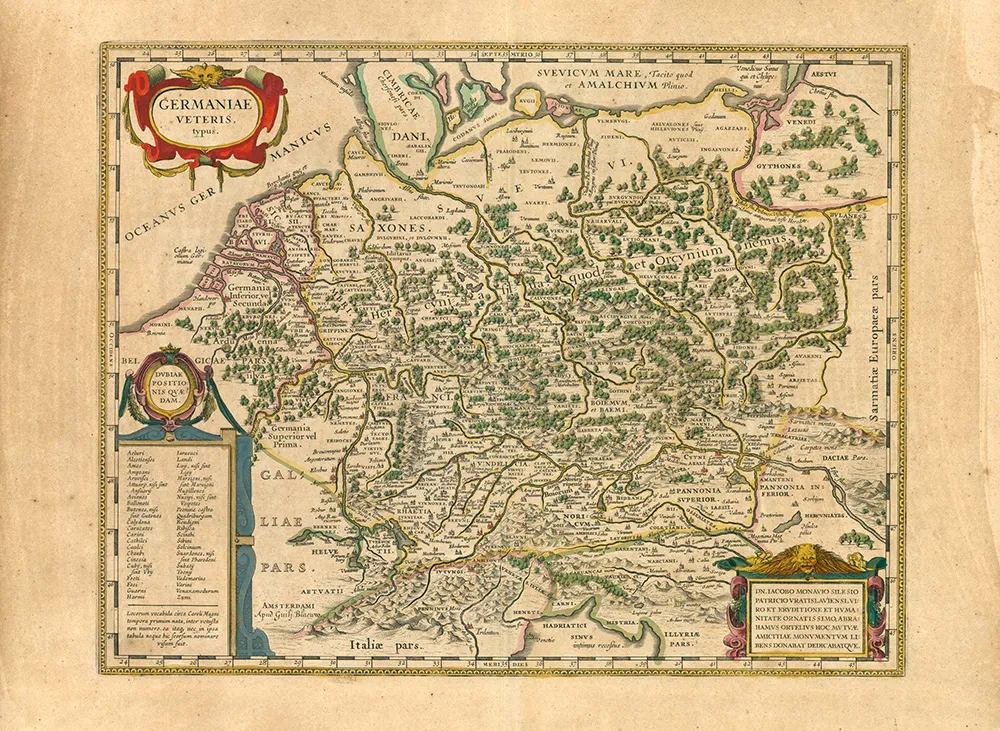

As early as the first century AD, the Roman historian Tacitus mentioned in his chronicles the land of Aesti. This fact was later confirmed in the 5th century by another Roman – Cassiodorus, who wrote that the Aesti people were Estonians. Despite the fact little is known about the territory they resided on, the sources mention peoples of a strong cultural identity and religious affiliation to nature.

Estonia didn’t need Viking raids – it had its own Vikings!

That’s right – the history of Estonia in the years circa 800 – 1200 has a chapter written by the Estonian Vikings. The Viking Age, as it is referred to, speaks of many battles and raids carried out by fearless warriors. Estonian Vikings are famously said to have kidnapped the queen and the future heir to the throne of Norway, Olaf Tryggvason. At that time, Estonia was not united as one nation, with several regions entering into a more or less permanent alliance.

By this time, the land has undergone changes. Settlements with forts were slowly swapped for developing villages, giving the beginning to the peasant culture of Estonia. Trade was swiftly developing, as well as there were advancements in farming. By the end of the Viking Age, Estonia was on its way to becoming a more contemporary European land.

Arrival of Christianity and Germans

The 13th century was the age when Estonia clashed with Christianity. As the Estonians were not overly keen to change their faith, which was strongly connected to nature, especially forests, a Livonian Order was founded in 1202. By 1217 the Germans conquered southern Estonia, which was incorporated into Livonia, just as was the faith of the neighboring Latvia. This meant a strong influence of German lords who, once they settled in the lands, continued having their say about the legal thought and social and cultural construct of the lands for close to 700 years.

Needless to say, that’s a very long time – they held longer than the Teutonic Order or any other force ruling over Estonian lands. The Livonian Order was led by bishop Albert von Buxhoeveden, who made a pact with the Danes inviting them to the northern part of today’s Estonia. The Danish invasion of 1219 resulted in the demolition of a fort known as Kaluri, and the construction of a new one. The Estonians named the new fort Taani Linn (meaning: Danish town – one of the possible versions of its name), which rightly so should sound familiar. The settlement became the later capital of Estonia and was known for the majority of its existence as Reval and Lindanäs. Its current name, Tallinn, was adopted in 1918.

Teutonic Knights take it all (as usual)

The Danes took the northern lands but not for very long. As a result of the 1343 Estonian uprising, which followed the death of the Danish king Christopher II and the political turmoil it caused, the lands of the Danish Duchy of Estonia fell under the control of the Teutonic Order. In the history of nations who had the dubious pleasure of having to deal with the Teutonic Order, the institution is known as a guest who would persistently overstay their welcome – even when asked, they would not want to leave. Ever. Hence Denmark, overpowered by its own troubles and pressed by the pro-German lobby, eventually sold the Duchy to the Order in 1346.

A failed attempt at complete dominance

To cut a long and very twisted story short – the Polish and Lithuanian Commonwealth had a huge grudge against the oppressive Teutonic State. Mastering strength and allied with additional forces, a breakthrough arrived in 1410 when the Commonwealth defeated the Order at the battle of Grunwald (also known as the First Battle of Tannenberg). This was a turning point in history, which led to the transformation of the State of Teutonic Order into the Duchy of Prussia with its first leader (and, at the same time, last Grand Master of the Order), Albrecht von Hohenzollern, paying homage to the Polish King, Sigismund I the Old.

Obtaining the lands as its fief allowed the Commonwealth to move further into the former Teutonic State territory. The kingdom’s efforts granted Livonia (now inclusive of Estonian lands) as its fief in 1561. They were surrendered to the Commonwealth by Gothard Kettler, the last Grand Master of the Livonian Order. The fief, however, was not inclusive of the northern part of today’s Estonia, which went under the rule of the Swedish crown and was known as the Duchy of Estonia.

Swedish domination…

The political situation in the entire Livonia was, however, not particularly stable. The land was also of interest to the Russian Empire and the Swedes, who were in constant conflict over the lands with the Commonwealth. Neither of the three clashing powers would easily give up. After a series of wars with Sweden, the Commonwealth did not secure influence over the northern lands of today’s Estonia and lost the vast majority of Livonia to the Swedish forces. By 1660 only one-fifth of the lands in the area remained under Polish rule. It seemed like all was settled. But, hey! What happened to the last player – Russia? It was patiently awaiting its turn.

… interrupted by the Russians

During the Great Northern War, everything changed. Swedish dominance and aspirations of being the leading power on the Baltic coast were challenged. As a result, a war broke out in 1700 that lasted 21 years. The peace left Sweden defeated, with the lands of today’s Estonia falling into Russian hands. The German nobles, who were still strong in Estonian lands, were getting along pretty decently with the new occupiers.

So much so that only about 2% of nobility was of Estonian background. Germans were in control, and Russians supported their efforts at keeping the Estonian nationals in the back seat. Any rebellion would have been quickly and efficiently nipped in the bud. Such imbalance could not last forever. When serfdom was abolished in 1816, the spirit of Estonians revived, and the nation started spreading its wings.

National awakening

The process was long and intertwined with the installation of new supremacy of Russia, eagerly supported by local Germans. When in 1739, the Bible was translated into Estonian, German Lutherans did not like it and banned the publication with the help of the occupier. However, as literacy was increasing among the natives of the lands, so was the understanding of Estonian nationality. The longing for the right of the nation to decide for itself was also intensifying. The russification process, which commenced in the 1880s and lasted for about a decade, only increased the resistance and fighting spirit of the Estonians.

First attempt at independence

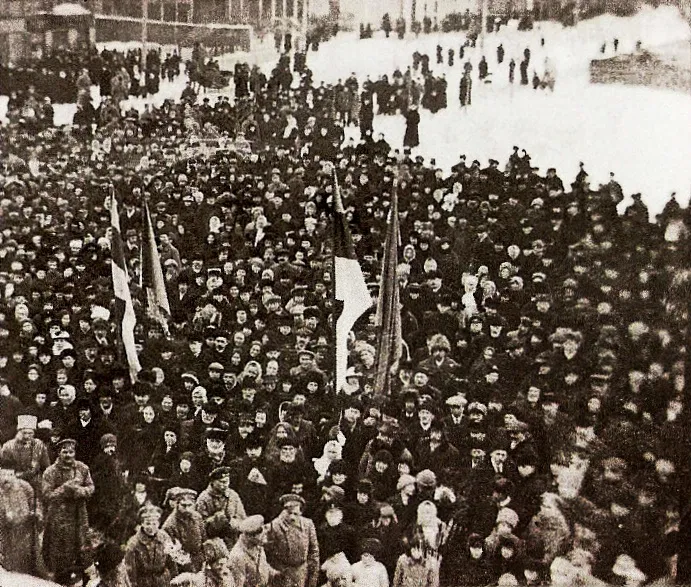

When the Russian Revolution of 1905 reached Estonian lands, the self-aware nation demanded more liberties and equal treatment in the face of the law. Most of the demands were not met, but the growing sense of community aided the cause. When towards the end of the First World War the Russian Empire was about to collapse, a provisional Estonian Government was formed in February of 1917. A year later, in February 1918, Estonia managed to issue a manifest of its independence as the Russian troops were falling back, and the German forces did not yet advance.

The Germans did not stay long and finally also retreated in November 1918. But this was not the end of the struggle for independence. The Bolsheviks tried to move back west and attacked the newly formed democratic entity of Estonia. With the support of the United Kingdom, the Estonians fought a victorious campaign which ended with a peace treaty signed in Tartu in 1920. By the power of the treaty, Russia forever waived any claims to the territory of Estonia. With fingers crossed…

Interwar Advancement and betrayal

The interwar period saw the rapid development of Estonian culture, language, education, and thought. National artists began to create, and the industry flourished. The nation was hoping to have finally reached peaceful security. Not for long. The Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, agreed upon between Germany and Soviet Russia, sacrificed Estonia to the Soviets. When the Second World War broke out later in 1939, Estonia was swallowed by Russia, despite its eager attempts at remaining neutral.

Russian troops entered the country in 1940 and the first year of brutal, barbaric treatment by the occupiers left Estonian society severely damaged. Suffice it to say that when German forces arrived from the West in 1941, most Estonian treated them as liberators, feeling relief the Russians were gone and hoping for the restoration of an independent Estonian state. These hopes, however, soon fell through when Estonians realized they were merely to become another province of Germany and simply were handed over to another overlord.

They resisted the occupier, with many Estonians fleeing for Finland and joining the Finnish forces instead of the German ones, but when the Russian threat rose back up from the ashes – large numbers of them returned and joined a fraction of the German SS forces in order to save their homeland.

Soviet occupation

In 1944 the war reached its turning point. Germans started to retreat, but the Estonians serving in the Estonian Waffen-SS division were allowed to fall behind and protect their land. And so they did. Unfortunately, the Soviets were too strong, and in 1944 they reentered Estonian lands. The people did not willingly want to accept yet another foreign reign and fought back. Similarly to Poland, Lithuania, and Latvia, Estonia established its guerrilla resistance forces known as the Forest Brothers.

The partisans tried to liberate the country, but in all honesty, there was not much they could have done to successfully repel the enemy. The era of Soviet rule brought about mass deportations, murders, and restrictive laws. Similar tactics to those observed in Latvia were used against Estonians, where large numbers of Russian immigrants were relocated to Estonian lands in an attempt to fade out the existence of Estonian nationals. By the late 1980s, the survival of Estonian nationality was critically threatened, but a change was in the air.

From a chain of hands to dropping the shackles

On August 23, 1989, Estonians joined hands with other Baltic States nations. Quite literally so. People of all three nationalities formed a chain from human hands, uniting the capitals of Tallinn, Riga, and Vilnius. The chain was over 600 kilometers long – one of the longest chains of this type in human history. This peaceful manifestation was what tipped the scales to the advantage of the long-oppressed nations.

Before this event, Estonia had seen some other significant moves towards reinstating the country’s independence, such as establishing Estonian as the official language in the land (January 1989). It took further two years until Estonia proclaimed its independence on August 20, 1991. Russians did not want to take the hint and, on the following day, tried to storm the Tallinn TV tower. They did so in order to block the free Estonian media from broadcasting, but the radio operators, who were at work that day, successfully defended the structure.

Free at last!

Three years of negotiations followed to see the last Russian troops leaving Estonia for good. On August 31, 1994, Estonia was finally fully free! The country immediately started building economic and diplomatic ties with the Western World. The country joined NATO and the EU in 2004. To put it into perspective – in the year 2023, it is still not full 30 years since the departure of the last Soviet troops and the fall of the regime.

And look where this brave nation is at now! The most digitalized European country with open and welcoming locals who are proud to share their unique culture, unspoiled nature, and delicious cuisine with anyone who wishes to get off the beaten touristy track and venture out to more northern destinations. If you, too, decide to head in that direction, you better pack your high heels! Estonians proved in their history to stand tall metaphorically, but the same applies in a very literal sense – they are considered one of the tallest nations in the world. Not a biggie – they are surely worth looking up to.