As soon as humanity learned how to cultivate the earth and grow its food, it seemed appropriate to thank Mother Nature (and the gods, of course) for her generosity. Although much is suspected and not much is known for sure about the origins of the harvest celebration, it is certain that in the times before Christianity, Slavic peoples celebrated the end of field works during the September equinox. Plentiful crops gave hope for the upcoming winter and naturally must have led to… epic parties.

In Poland, the tradition of dożynki (celebrations of completed harvest) is longstanding and very much alive. And advertised. Dożynki have this magical power of gathering together those whose hands look after the fields and those with whom they share the bounty collected from the land. Just as it has been over the centuries. Let me tell you more.

Dożynki: Landowner’s treat

Sometime around the 16th century, celebrations of harvest in Poland started taking on a more organized form. The holiday became a way for the landowners to thank the peasants for their hard work in the fields. They would invite them to their estates, where they would throw a feast with music and dancing. Certainly, an event worth working for and not likely missed by the locals!

As time passed, towards the end of the 19th century, when the field workers were becoming, well, simply more decadent, they decided it would be better to organize their own bash without such involvement of the landlords. Oh, but the occasion was too good and popular to let the opportunity for emerging institutions to have their slice of the cake. During the interwar period, celebrations became even more official with the involvement of local authorities.

That’s when they transformed and received a ‘new look’ with fairs, performances, and exhibitions. Very similar to the way polish harvest festival is organized today. As with every significant festival, a multitude of customs, traditions, and superstitions arose around the occasion.

Join the end with the beginning… or else!

After harvesting the last crops from the fields, the ceremonial coronation of the harvest commences. You may say that the central part was focused around a… wreath. Traditionally, it was made in a crown shape, adorned with nuts, rowan, apples, and sometimes even a live bird! It was essential (and still is) to use the last culms of cereal for its construction.

Why was it so important? The wreath was then taken around the fields and taken to the landowner, where he would thank the harvesters with the feast. It was placed in the barn and waited until the following year. When the time for sewing the fields came, the grains extracted from the wreath were added to the grains used for that first sowing. It was a symbolical union of the end with a new beginning and good fortune for plentiful crops in the following year. This tradition is still practiced by many today.

But making that wreath was not as simple as you may think. When harvesting, men would leave a small stretch of crops cutely called ‘a quail’. It was then reaped by the best male reapers and handed over to the best female reapers, who would, in turn, weave the wreath.

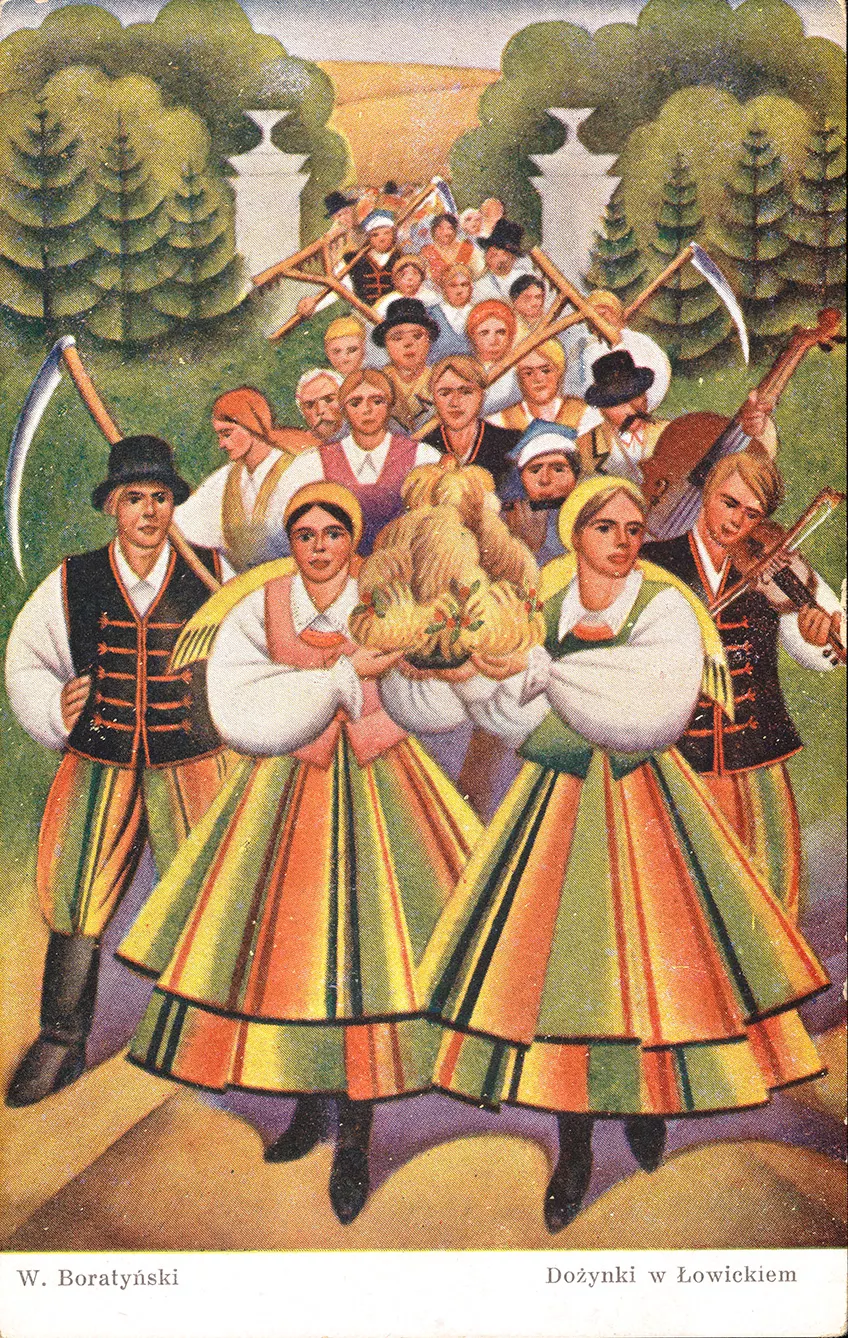

The wreath was then taken to church and blessed during a special thanksgiving mass. They would also bring a loaf of bread baked from flour made with the crops from the previous year. That bread was also blessed. Afterward, the wreath and the bread were taken to the landowner (or later, the rich farmer responsible for throwing the dożynki party) in a colorful pageant with music and singing. The host would welcome the participants and receive precious gifts. Harvest was officially over.

Times, they are a-changin’

Although poorer crops one year don’t necessarily (and thankfully) mean famine these days, people still pay attention to the celebrations of harvest, giving thanks to God and enjoying the communal effort. The tradition of annual harvest festival did not fade away. Not at all!

Most of what was said before can still be experienced today. Perhaps many smaller customs are not commonly practiced, but these changes are honestly relatively small, with new traditions emerging in their stead. The pageant may not be as colorful and celebratory as it used to be, but it is still practiced. As is the tradition of baking and blessing the special loaf of bread. Having a dożynki host. Dancing, singing, and feasting.

The tradition of the polish harvest festival is so strong that it was even practiced during the communist times, albeit back then, it was used as an opportunity for political manifestos. After the fall of the regime, traditional understanding of these celebrations, which were always connected to the spiritual, were reinstated and last. Even the head of the Polish State gets involved, with the traditional Presidential Dożynki held annually, usually in the village of Spała. Inaugurated by president Ignacy Mościcki in 1927, they were reinstated after the Second World War by President Aleksander Kwaśniewski in the year 2000, although with a more regional character. President Lech Kaczyński brought the celebrations back to Sapła in 2009, where they were held nearly every year until the pandemic.

Another visible change can be seen in the wreaths. They have become more elaborate and function as a way to sum up, the passing year. The constructions you can see are breathtaking. True pieces of folklore art! And where there is folklore, there is… sense of humor. Straw can be used not only for making wreaths. Should you find yourself passing through local Polish roads sometime after the Feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary (15 August), you will undoubtedly see big constructions made out of hay placed around the countryside.

These ‘witacze’ [the welcomers], as they became known, invite passers-by for local dożynki celebrations, informing them of the date they will be held. They are mostly made to look cute, funny, and eye-catching. They became so characteristic and important for the local communities that some communes now run an annual competition for “The Best Dożynki Welcomer.” And trust me when I say – they indeed are a sight!

Dożynki: An informal New Year’s Eve

Dożynki has another important function for rural communities. As life in the countryside revolves around the fields, it is an opportunity for people to look back at what has happened in their lives and the world since the previous harvest.

It could not be visible more than during the polish harvest festival of 2020 (the first year of the pandemic) and this year when the majority of communities pay tributes to Ukraine and manifest their solidarity with their neighboring Ukrainian farmers. As it has been said many times before – countryside communities are the salt of every nation. Don’t decline the invitation to enter their world and join in their most important celebration too hastily.