Ernest Malinowski was born in 1818 in the Podolia region of what is today part of Western Ukraine and Moldova to a wealthy family of Polish nobles. His parents were involved in the patriotic movement, raising their children in the same spirit. Despite some sources saying Ernest took part in the famous November Uprising of 1832, at that time, he was only 14, and it was his father and older brother who were more actively involved. Nevertheless, after the failed attempt at restoring independence, the Malinowski family was separated like many other families at that time. Ernest’s mother stayed with her youngest son in Volynha, while Ernest and his brother and father left for Dresden and, from there, for France.

Torn apart

Ernest Malinowski graduated with honors from the famous technical college École des Ponts et Chaussées. His brother, Rudolf, was also a talented engineer, and they soon found stable employment with the State. Things got a little complicated when Ernest and his brother were sent to (then newly French) Algeria in 1839. They both disliked the idea; however, Rudolf assimilated and, in the end, stayed with the job, while Ernest rebelled and returned to France within months.

He was labeled as “the difficult one” and from this moment, despite his talents, found it difficult to advance in his career. Perhaps this was what made him take the opportunity to emigrate to Peru in 1852 – especially as by then, his father had been dead for two years, and his brother was still in Algeria. The task he initially received from the Peruvian government was to draw up the plans and supervise the construction of new roads and draw maps. But, in the end, his role grew to something much greater.

Railway – the Queen of Transformation

In the late 19th century, the railway was considered the most important mode of transportation, capable of transforming the fate of entire countries. Peru was no exception. Malinowski designed and supervised the construction of the first railway tracks in that country, which became the ticket to the recognition he deserved.

But before his great breakthrough, he managed to secure himself the title of the national hero of… Peru. Malinowski designed and supervised the construction of fortifications in the port, as well as took an active part in the battle that was victorious for the Peruvians. (Fun fact: the Spanish also considered it to be a victory. Perhaps the most satisfying end to a conflict in the history of mankind.) Anyway, apart from victorious titles, Malinowski was also granted honorary citizenship of Peru on account of the battle.

But let our train of thought return to the initial tracks, pardon the pun. In 1869 a famous investor, Henry Meiggis, approached Malinowski with a request to design a railway track that would join the central part of the country to the coast. And it was a challenge since the way was naturally blocked by the Andes. A piece of cake, for Malinowski that is.

Making the impossible possible

His design was met with… a lot of criticism on the British part, to say the least. The British engineers laughed at Malinowski’s idea to drag a railway through the Andes at an altitude close to 5000 meters above sea level. “Preposterous!” they said, chuckling with laughter over their five o’clock tea with a compulsory drop of milk. Thankfully, the Peruvian government was of a different opinion, and the construction began in 1870.

Malinowski did not stop at designing the track. He supervised the entire process. His dedication is something we don’t see these days – he slept where the workers slept, high up in the mountains, where the temperatures ranged between -14 Celcius and night and + 26 degrees in the daytime (6.8 and 78.8 Fahrenheit). He personally inspected all cavities, took samples of the rocks, and made sure all groundwork was carried out as it should be. He was fearless and… fair.

He made sure all of his close to 10,000 workers were treated with respect, received their wages, and worked in conditions as safe as possible. The enterprise was so bold that many of them lost their lives due to accidents and diseases. And to nip all speculations in the bud – Malinowski and Meiggis did not strike a goldmine with the contract. Troubled by war, Peru discontinued funding the railway. This did not stop Malinowski and Meiggis, who funded a large part of the works from their own pocket and did not earn a penny for themselves.

The Central Trans-Andean Railway in numbers

When the project was finally completed in 1893, the world reacted… with yet another sneering reception. “Completed? Way up there, in the Andes? Yeah, right – and my name is Napoleon Bonaparte!” This is no laughing matter – the engineering world’s problem of believing in such a success was serious. It took many visits from ambassadors and experts who traveled to Peru and had to be taken on the journey on the sky-high railway to finally believe in its existence.

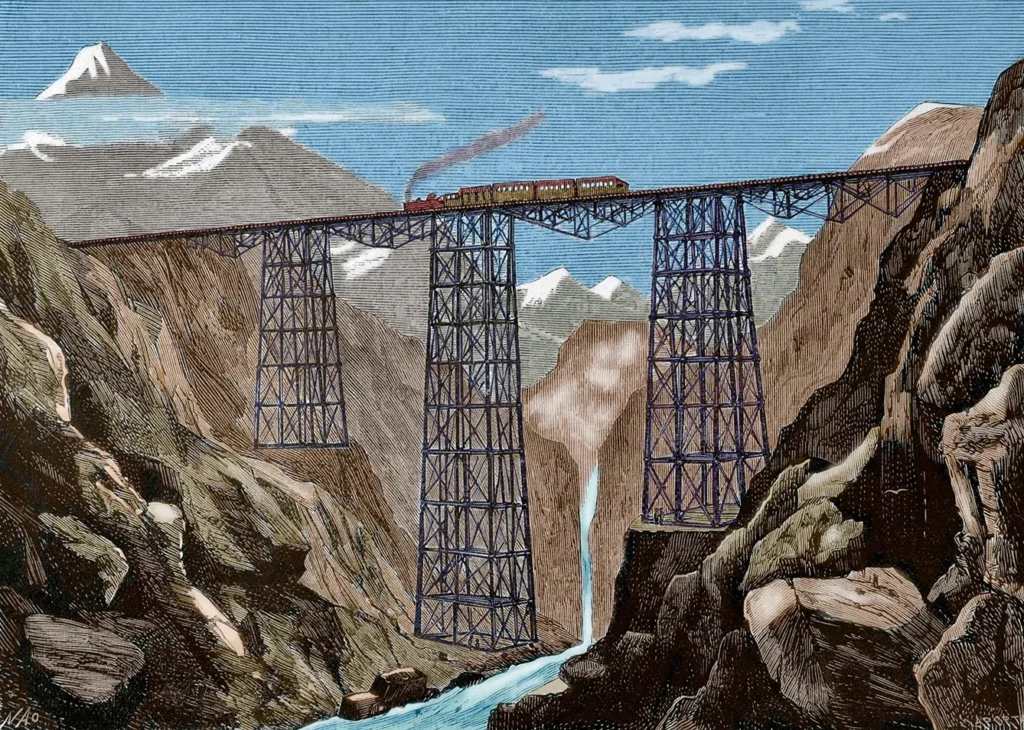

To be fair, it is hard to blame them. The Central Trans-Andean Railway was, until 2006, the world’s highest-situated railway – at its highest point reaching the altitude of 4784 meters above sea level. The 218-kilometer route runs through virtually vertical parts of rocks and comprises 63 drilled tunnels length of all the tunnels amounts to over 6 kilometers (the longest tunnel is 1200 meters long).

The construction is complemented by over 61 ridges and flyovers. The most impressive one, the Verrugas flyover, is the longest on the route (approximately 200 meters) and rests on three metal beams, of which the tallest one measures a record-breaking (for that time) 77 meters. And all that was achieved by a group of people, who carried supplies and materials on their backs and with the help of animals.

Forgotten hero?

Malinowski died in Lima of a heart attack at the age of 81. His death was recorded in all main Peruvian newspapers, but also abroad (Poland, France, and Great Britain, to name some countries). He was buried with honors reserved for national heroes. Today, efforts are made to restore the name of Ernest Malinowski to its well-deserved glory. It would be nice if he was equally recognized in the collective consciousness of the nations, as are the Kardashians. After all, he is an epitome of a man who reached the stars in the fight for his dream. A dream that last and serves new generations of people.