“No one in 1916 could believe a woman might be in charge of building a house – including myself,” recalled Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, at age 100. Yet, in 1916, a nineteen-year-old girl became the first female student of the famous Kunstgewerbeschule, a colleague of such figures as Oskar Kokoschka and a protegé of Gustav Klimt himself.

As an architect, which she soon became, she studied under Oskar Strnad and then worked with Adolf Loos – the former was a pioneer in social housing who contributed to making Vienna the city it is now, with its exceptional standard of living. The latter – a successful architect known for his idea that ‘ornament is a crime.’

A Frankfurt Kitchen from Vienna

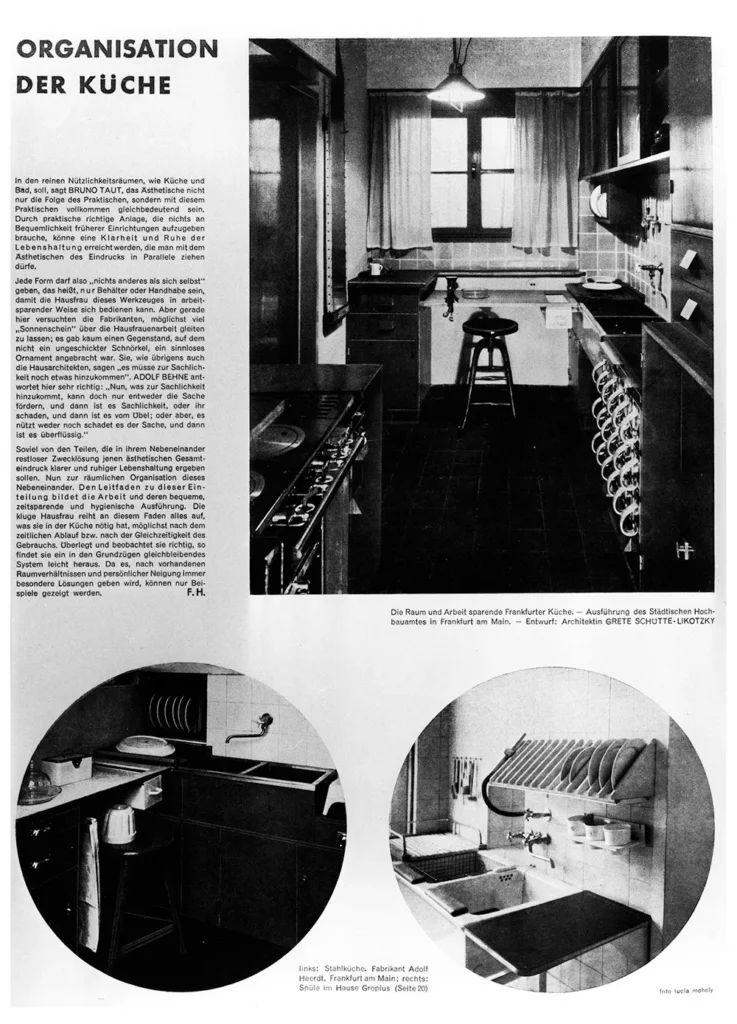

Yet what made her famous were not buildings but something modest yet revolutionary – a kitchen, namely – the Frankfurt Kitchen, a.k.a. kitchen-laboratory. Frankfurt am Main was developing rapidly in the 1920s and followed the idea of New Frankfurt – city housing expansion to accommodate workers during industrialization.

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky oversaw public buildings, schools, and preschools, but also housing. And one idea of a modern building of that time was to create modules to optimize spaces as both comfortable and cheap to build. Modern living spaces – with facilities such as running water or sanitation, required a new kind of flat plan – one including a separate kitchen and, usually, a bathroom. And modular kitchen could be furnished with prefabricated furniture so that every working family could move into a decent standard of living.

To design the new kitchen, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky turned to research made by none other than Frederick Winslow Taylor. As in ‘Taylorism,’ the idea of almost scientific ergonomic optimization to maximize the effectiveness of work.

Taylor analyzed workspace and tool ergonomics so that his workers could work as machines – everything handy, everything optimized for work speed. Though his ideas sound rather dystopian in today’s ear, one part of his legacy is the simple idea that tools should be designed to fit the hand, not the other way around.

Schütte-Lihotzky’s drawers

But Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky took Taylor’s research to another level, and there’s an issue of gender: as Taylor worked to maximize his income by turning his workers into robots, the Viennese designer used his research to facilitate the invisible work of women around the household.

The modern Frankfurt Kitchen was modeled after a dining railway car. Fitted with a sink and oven, it somehow followed the idea of an assembly line, taking into consideration a sequence of steps usually taken during house cooking.

Drawers – and lots of them – were the household equivalent of a cook’s mise-en-place, and even light and handy stools were designed to improve the cooking experience. Even the color – blue-green – was scientifically based, as it was supposed to repel flies. Hence the name – the kitchen-laboratory. Moreover – the project actually took off, and some 10 thousand such kitchens were soon in use in Frankfurt.

After her acclaimed design, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky moved to the Soviet Union (not entirely contrary to her political beliefs) to support Stalin’s five-year plan. She co-designed the Soviet city of Magnitogorsk, where urban development literally exploded from a few barracks due to industrialization.

She left the Soviet Union due to Stalin’s repressions and engaged in anti-Nazi activity. She was eventually arrested and sentenced to 15 years in prison, but she was later liberated by the US Army.

Living for a time in Sofia, Bulgaria, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky moved back to Austria in 1947 and remained an architect, though not a favorite of the Communist party. Both professionally and politically active, she remained an important figure in post-war Vienna.

Her grave in the Central Cemetery is modernist, modest, and does not commit the crime of ornamentation. She died 5 days short of her 103rd birthday, she saw dozens of revolutions in kitchen appliances and trends, yet most modern kitchens are strikingly similar to the original 1920s design. As many architects like to be commemorated with the grandiosity of their buildings, she is commemorated with an idea.