Of course, fame does not usually come from just doodling unicorns and rainbows. How can it be that a man, who all his life was homeless, never had a day job, and was often seen begging could, at the same time, become one of the finest representatives of the naïve art movement? Who was Nikifor Krynicki?

Bare necessities

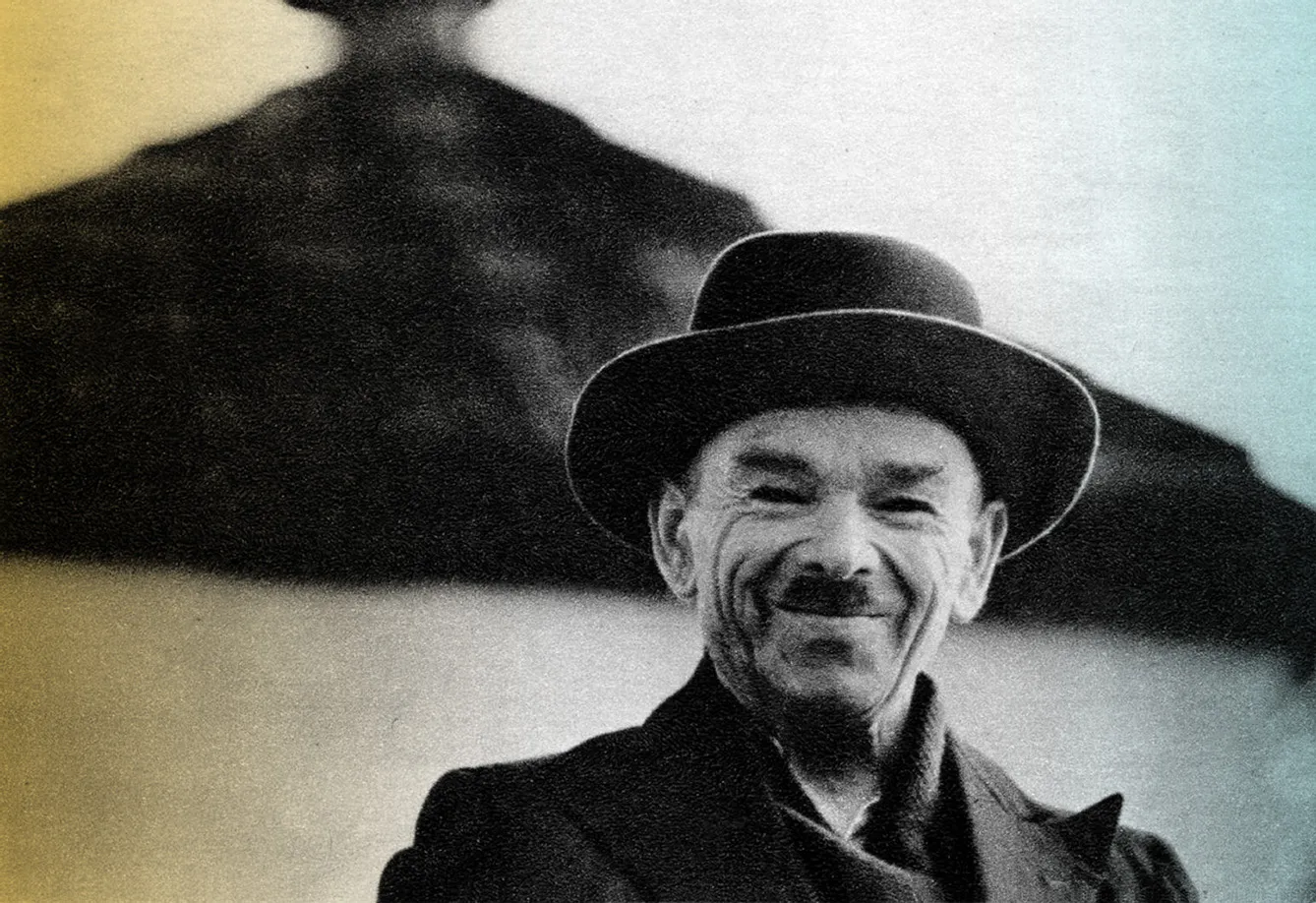

One who wants to briefly tell the story of one of the most encaptivating Polish artists goes on a head-on collision with a paradoxically near-impossible task. There is not much that is known for certain about Epifaniusz Drowniak (the real name of Nikifor Krynicki). Ironically, the meaning of his given name, the one who came to this world, pretty much describes how he was perceived by most of his contemporaries – a bizarre, homeless individual, more likely mentally challenged.

However, Nikifor was much more than met the eye. Born of a poverty-stricken, basically dumb and deaf mother with Lemkos roots (an ethnic group originating from today’s Ukraine), he suffered from hearing and speech impediments which made it difficult for him to communicate with other people (not that many paid much attention to an odd fellow selling small, watercolor paintings). It is not known for sure what year he was born, but many assume 1895 as his birth year. No one knows for sure who his father was. Some claim he might have been a painter who visited the wonderful spa town of Krynica-Zdrój and fathered Nikifor, but this is mere gossip. Orphaned at a young age, Epifanius Drowniak turned to the only thing he loved doing and felt a calling to do – painting.

Souvenir, Madam?

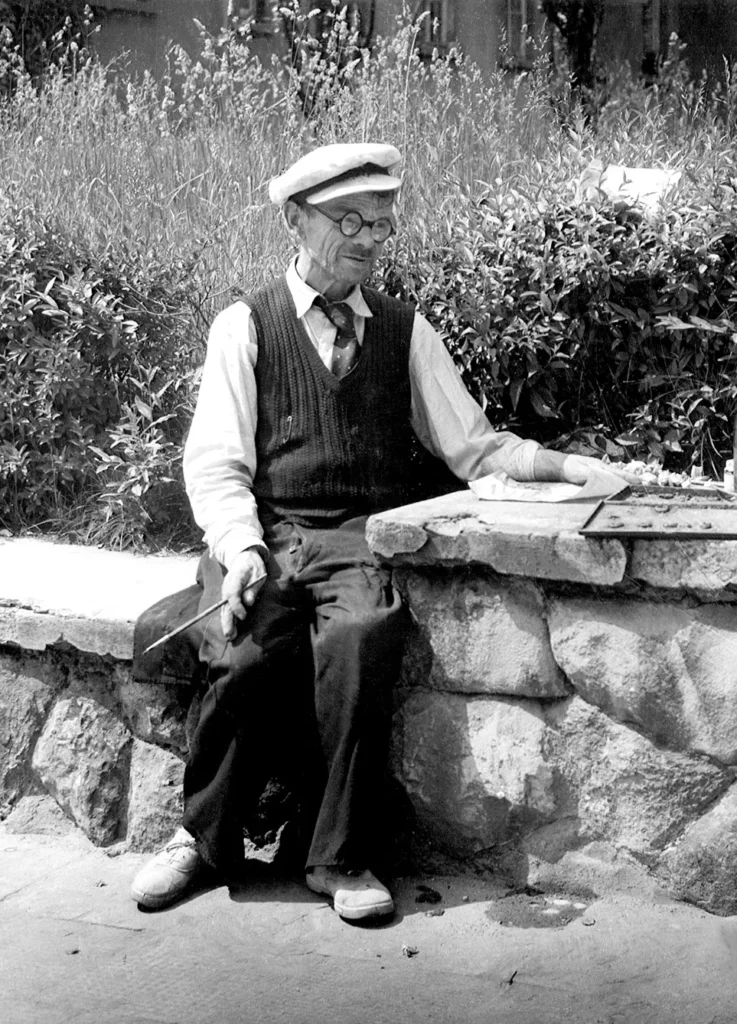

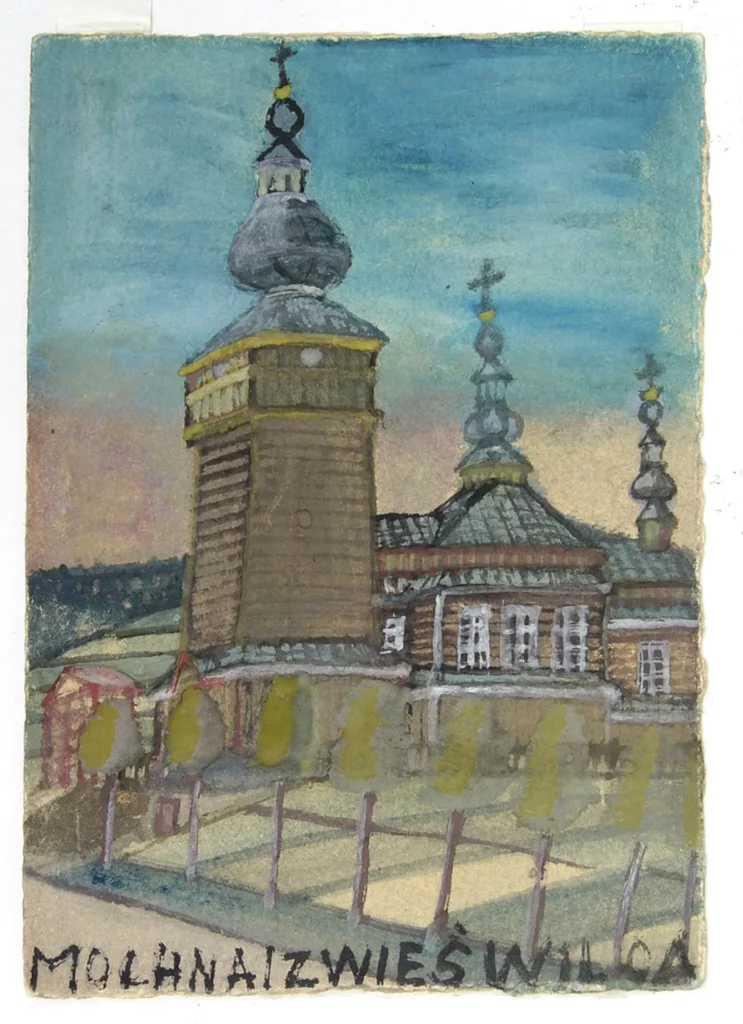

When he was a little boy, his mother, who raised him an Orthodox Christian, would take him to church, and, pointing to the many wonderful icons of saints, she would tell him, “Your father painted those.” This seed fell on the fertile ground of Nikifor’s gentle soul and grew into a dream of once becoming a famous painter. Orphaned at a young age, Nikifor was selling his works as a way to sustain himself. He was most often seen sitting at a wall by the church where he would paint and sell his paintings – little souvenirs from Krynica-Zdrój.

Confined in his rather unassuming posture and struggling to speak, Nikifor would express the depth of his thoughts in his works. And he was a very prominent artist. It is estimated that he painted more than 40,000 compositions during his life (of which no two are the same) – an astounding number even for the most gifted painters. But for Nikifor, his art was the way of life and a calling.

He truly believed that he was obligated to create and share his talent with the world. He once said that his art was “a conversation he has with God,” and indeed, he clearly enjoyed a profound spiritual life. His works often depict topics of metaphysical content – often portraying saints or Nikifor himself in heaven. It is said he felt best at his orthodox church, where he could be found conversing with the images of saints depicted on the icons.

These were far more complex notions than one would expect of a supposedly mentally challenged man, proving just how misunderstood Nikifor must have been. But apart from his transcendental deliberations, Nikifor had one muse – a city that stole his heart and became his commonly used surname: the town of Krynica-Zdrój (hence: Krynicki – of Krynica).

Simplicity used to portray depth

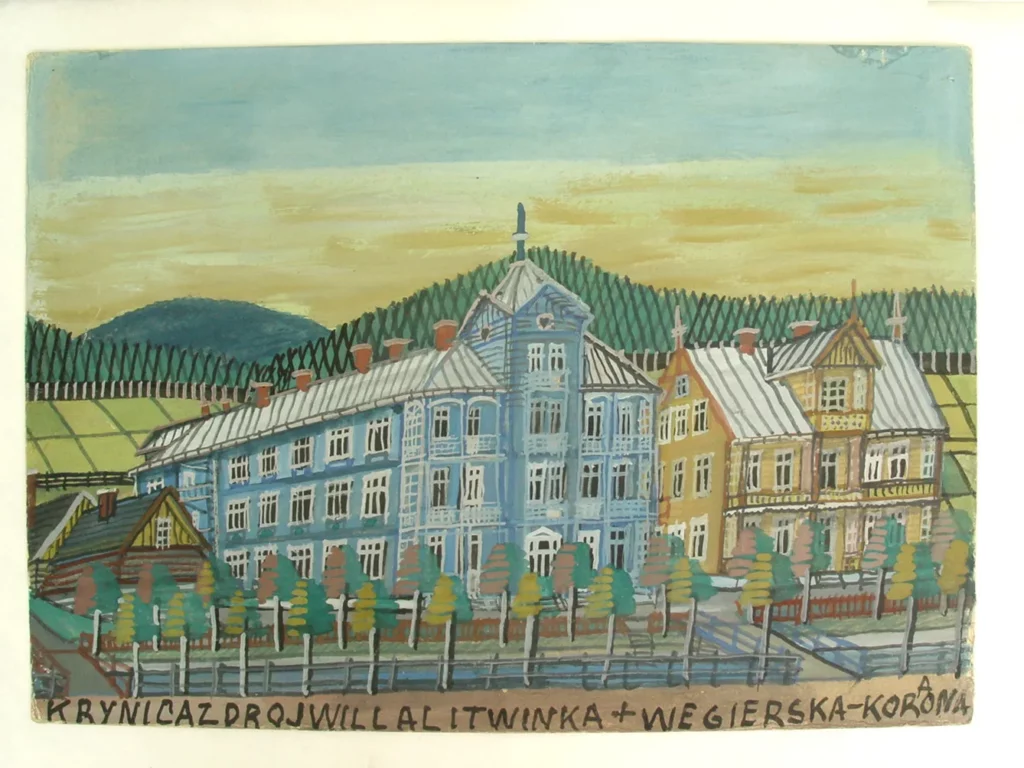

Krynica-Zdrój, a not-so-big spa town in the south of Poland, is a charming place, and no wonder Nikifor would obsessively paint his town. In 1947, due to his Lemkos roots, he was thrice forcefully relocated to the Recovered Territories, namely the west of Poland. Yet each time, he would return to Krynica-Zdrój… on foot! To give you a perspective – if you wanted to walk from the most northwestern city in the Restored Lands, Szczecin, it would take you about six days of constant walking to reach Krynica-Zdrój (covering a distance of over 700 kilometers or ca. 440 miles).

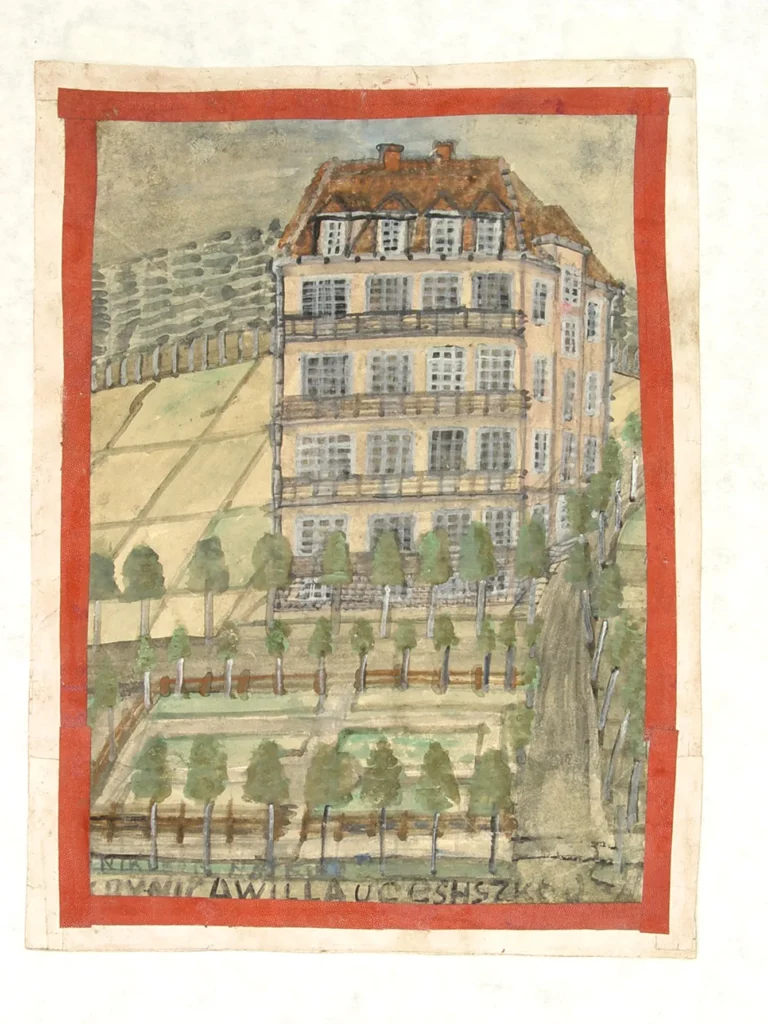

But that was where he felt at home. His pictures of Krynica and the town’s everyday life granted him the name of an exceptionally gifted naïve art artist during his lifetime. Every work is carefully detailed, with colors masterfully blending through their different, warm shades. His art is not simple – it is simply free of fluff. His pictures offer his perception of the charming spa town and have been described by many – artists, critics, and merely the public – as hypnotizing and encaptivating. It is bizarre how you find yourself glued to a seemingly straightforward depiction of a town’s square or men at work. But this invisible layer, the soul Nikifor poured into his works, weaves a story transmitted by his palette straight to your heart – one you get immediately lost in.

Master of… recycling?

Nikifor was very practical. He was poor, as he did not have the head for business. He would sell his works at meager prices, even after gaining recognition. Many were sold to art connoisseurs who would take advantage of Nikifor’s lack of money sense so they could later resell his works for a much higher price. So how could he afford to produce so many paintings? Well, we quite possibly might be looking at a true artist-pioneer in the successful recycling of materials.

Nikifor painted on notebook covers, official forms, and any other suitable paper he could grab hold of. He did not spend gazillions of dollars on top-end pains and tools. Instead, he painted using the cheapest watercolors and paintbrushes available – think supplies you might find in a first-grader’s locker. And he created with a passion similar to that of a child.

His art is honest, depicting the world with a child’s piercing perception. Unlike Van Gogh, Nikifor Krynicki was lucky to have been recognized by his contemporaries. First discovered by a pre-Second World War artist, Jerzy Wolff, he held one exhibition in Paris, but the bloody arms conflict halted further possibilities. Post-war, he had some national exhibitions starting with one in Warsaw in 1949, followed by a return to Paris in 1958, where he successfully captivated viewers, then traveling further to Amsterdam, Brussels, and Israel, to name a few destinations.

But these events did not turn his life around. Nikifor remained homeless and, in the last years of his life, was cared for by artist Marian Włosiński, who provided him with shelter, drawing materials, and companionship. Włosiński took over 300 photographs of Nikifor and sacrificed his own ambitions to preserve the extraordinary talent of this humble old man.

Shunned and admired

The story of Nikifor Krynicki is full of contrasts and paradoxes – much like his art. Once chased away from the Krynica-Zdrój’s promenade reserved for wealthy guests, he was later happily welcomed there by passers-by who wanted to meet the man whose name was becoming famous worldwide. His works of art on recycled pieces of paper and created using the simplest materials were, in the 1950s and 1960s, a watermark used in high society to mark those who genuinely knew something about art.

He dreamt of owning a house, part of which he would have turned into a gallery of his works, where he would be able to welcome other artists to talk about art. Alas, this dream only came to fruition after his death, with the creation of a museum dedicated to his art in one of Krynica-Zdrój’s most lovely villas – one the artist himself could never have afforded.

The genius of his style can be best appreciated when compared with false copies of his works that lack that Nikifor quality and, although objectively similar, look dull and childish rather than encaptivating with a child-like perspective. But don’t take our word for it – one look at Nikifor’s works, and you might just be dragged into the rabbit hole, entering deeper and deeper into Nikifor’s mysterious, spirited world.