While the Bulgarian state tourist monopoly Balkantourist began its successful march to affirm the strong position of Bulgaria on the international tourist market in the 1940s, Romania waited until the 1960s to hop on the marketing ship and looked with envy at its northern neighbor. But soon, the arsenal of techniques was employed, and the people who got the job were the right ones: female beauties, a Romanian dictator, and Count Dracula.

A long way to tourism in socialist Romania

Romania spent the early post-war period struggling to maintain stable power. But in the late 1950s, the internal situation allowed us to take further steps, and these were quite obvious: development required technology, technology required imports, and imports required hard currency. Who could bring it? The obvious answer was: tourists.

This was especially true since Bulgaria, Romania’s neighbor to the north, by then had hundreds of thousands of visitors from behind the Iron Curtain, which was just about to loosen anyway, and had created a firm image of a socialist paradise – with famous national cuisine and colorful pictures of tourist luxuries along the coast.

Meanwhile, Romania in the early sixties still tried to lure tourists with guided tours on especially successful state farms and perhaps some museum highlights.

For the Romanian socialist elite, opening to the West was a conundrum. After all, the capitalist West was, well, capitalist, and letting its citizens in posed a threat, both in terms of foreign intelligence as well as demoralization of the Romanian people. And, in going back and forth with tourism policies and the eternal struggle between hardcore communist and hawkish technocrats, Romania took a few interesting moves.

Dracula as a tourist attraction

One of the examples of the struggles was Count Dracula, the legendary ruler of Transylvania. Famous throughout the whole XX century, after Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, he remained widely known through dozens of movies, from which more than one had a cult status.

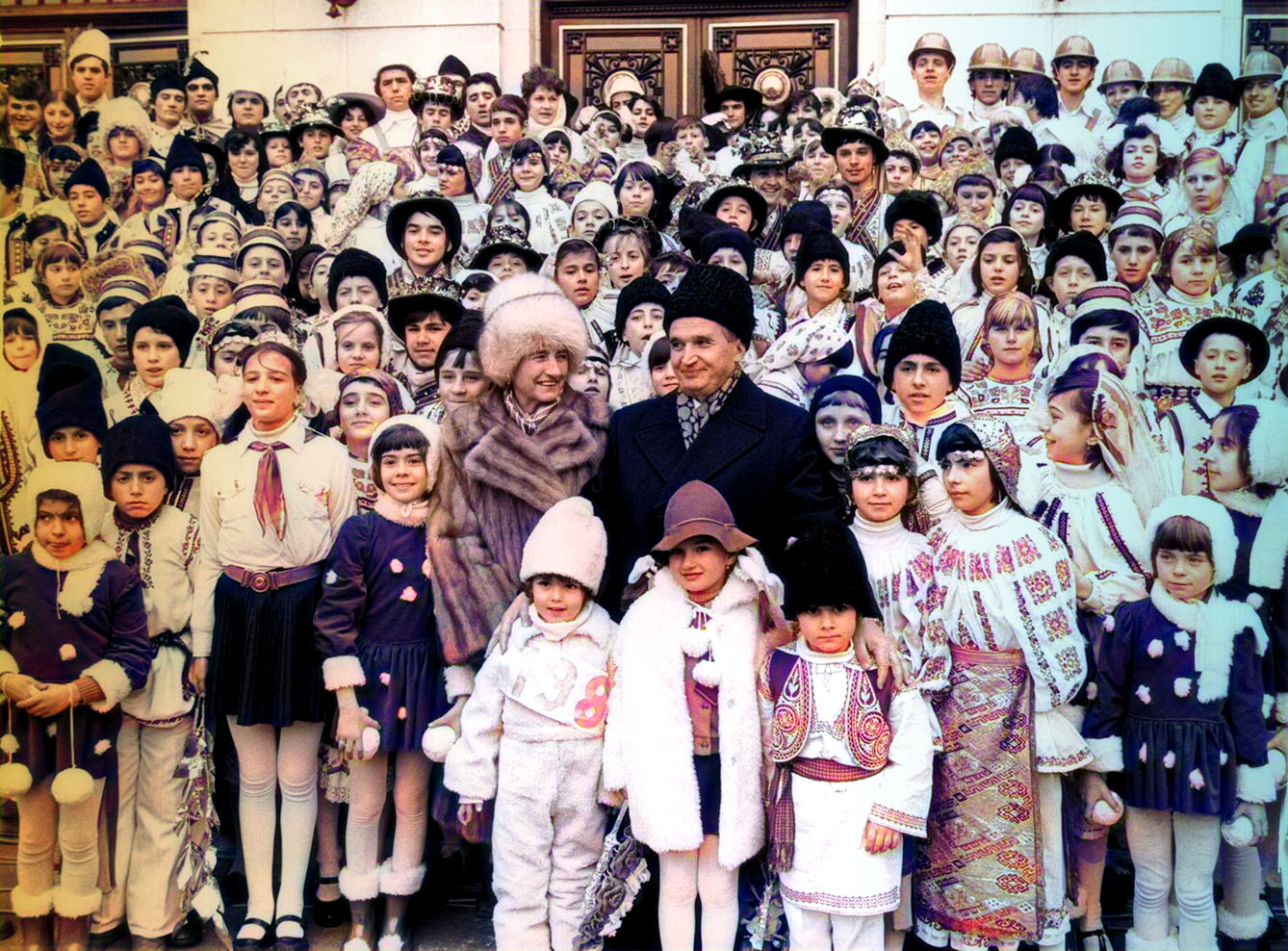

During 1970s, Romanian tourist pamphlets used to lure tourists with long-legged models. In 1980 its cover featured Elena Ceaușescu instead

Little there is to wonder that in the 1970s, when international tourism took up, and some thaw in East-West relations could be seen, the Western tourist industry answered the demand for trips to the root of vampire fantasies. Among them was a tourist magazine Viajar from Barcelona, which invited Spanish people to ‘discover the route of Count Dracula’ during a two-week trip. Also, American General Tours, in association with Pan Am Airlines, offered an ‘In Search of Dracula’-themed excursion.

There was yet a problem to which Dracula’s ads finally fell prey. Although dollar tourists were very welcome in the seventies, and by the late years of that decade, Romania published guidebooks in English, French, and German, the Transylvanian tours were uncomfortable in two ways.

The problem of Transylvania

One was that it presented the country as a kind of ‘savage’ instead of exposing the achievements of Socialism. Besides, following Dracula’s route included some Christian faith relicts, also uninvited in the official narrative.

The other was a bit more sophisticated: Transylvania was kind of a separate region, including the foreign ethnicity of Transylvanian Saxons. They were basically German, settled from the early Middle Ages, called Saxons as every German was called around back then. They had even their quite firm connection with Eastern Germany and, even worse, the Western part, largely benefiting from this contact. So, one-region destination tours were uninvited when it came to regions that were separatist.

Now that the Dracula trope was discouraged, technocratic travel marketers were forced to accent other pleasures that could tease Westerners. And there was yet another obvious prize: the golden sands of the Black Sea and the tourist luxuries that benefited Bulgaria so much.

Romania’s socialist beaches

In advertising them, the Romanian tourist authority, NTO-Carpathian switched from guidebooks to pamphlets ad booklets. The late sixties saw a paradigm shift in the quarterly to be distributed in hotels and airports, called Vacances en Roumanie.

In the 1970s, it was used to advertise practical and less-cultural, more-lifestyle aspects of titular vacations. It stated that along the Romanian coast, night clubs waitresses had to have ‘attractive legs and move graciously’ and ‘all-female personnel in Venus were selected through beauty pageants.’

Yet even that had to stop at some point. The problem was not in the over-sexualization of women, given that sexism was hardly ever a problem in Eastern Bloc. But again, the image of morally liberal hospitality offered was contrary to the official prudish Communist narrative. In effect, the 1980 cover of Vacances en Roumanie presented neither long-legged bunnies nor sunny beaches but instead featured Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife Elena.

Once again, tourist-luring techniques lost out to official Romanian socialist ideology. But then again, 1979 brought a fuel crisis that strongly impacted Socialist countries, and the subsequent Afghanistan war made Iron Curtain fall down again. Black Sea coastal Romania never managed to match its northern neighbor Bulgaria in tempting Western tourists. At its peak in the late 70s. it hosted less than 800,000 of them a year.