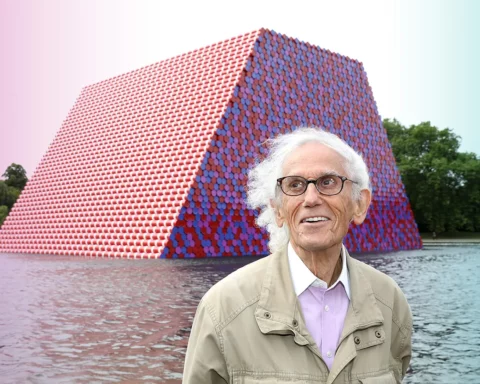

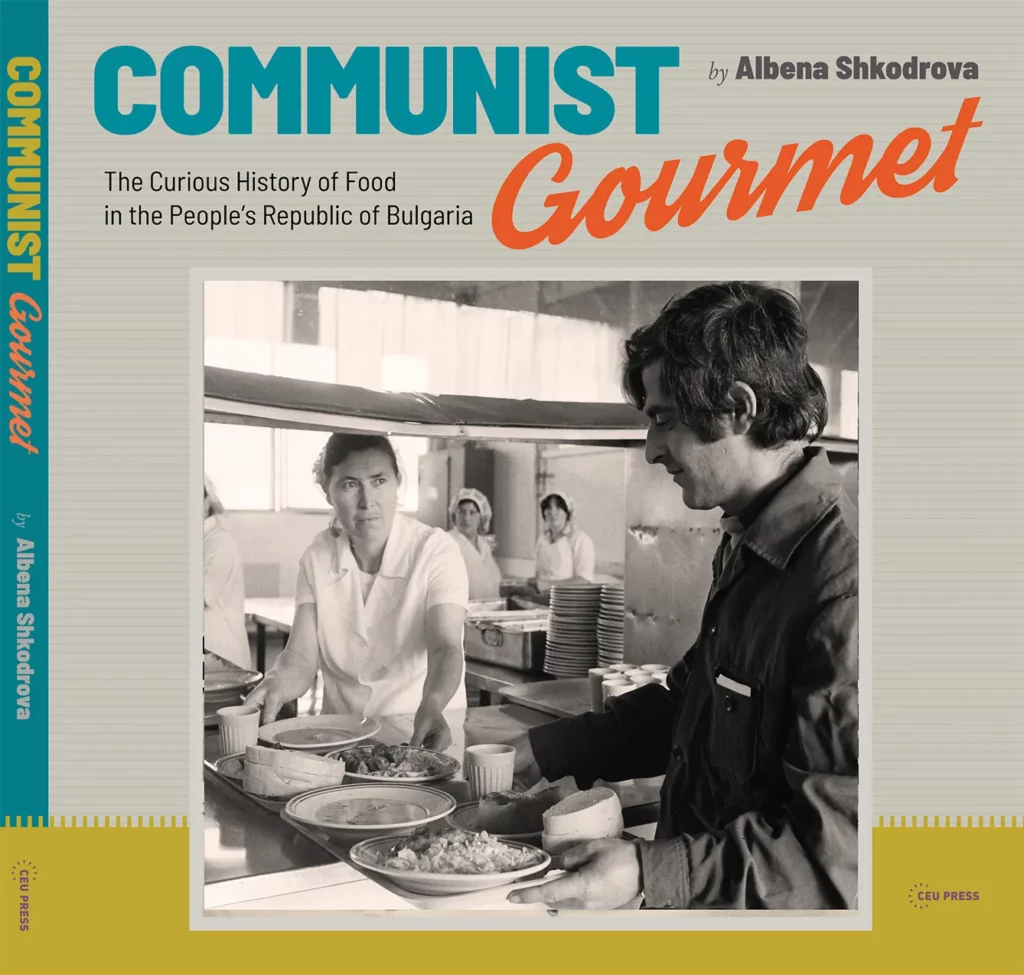

Dr. Shkodrova’s book gives an in-depth account of how the communist regime determined the Bulgarian people’s everyday food experience. Besides being a writer, she is also the Chair of the Bulgarian Food Studies Society, Around the Table. Dr. Shkodrova sat down with 3Seas Europe to tell us what was lost from the table – and what was later recovered -during Bulgaria’s 45 years behind the Iron Curtain.

GG (3Seas’s Galina Ganeva): Is there a communist food legacy in Bulgaria, and the wider region for that matter, and how does it manifest itself today?

AS (Dr. Albena Shkodrova): The communist period has a strong imprint on today’s menu, cooking practices, and tastes in Bulgaria, of course. It occupies 45 years of history and the generations that shaped their habits during this period are still alive.

GG: What did that process look like in Bulgaria?

AS: Socialist nutrition science was touted as very revolutionary, but it is not. It borrows a lot from the ideas of nutritionists of previous decades, and it is not radically different from Western views on nutrition during the same period.

Socialist countries, for example, had a persistent policy of preaching the benefits of eating meat. The socialist regime in Bulgaria regularly sought legitimacy in the growth of meat consumption. At the root of this obsession is the view that meat was the privilege of the rich, and the communist egalitarian state should make it available to all. But meat proteins are also considered the most efficient “fuel” for the socialist worker, who must be kept in excellent shape because he carries the general socialist economy on his shoulders.

But if the way in which the benefits of meat are explained is specifically socialist, the attitude towards it is not. The whole world discovered the industrial production of chicken and pork in the 20th century, and per capita consumption rose enormously between 1961 and 1990. In fact, even within Eastern Europe, Bulgaria remains at low levels of individual meat consumption. For example, at the absolute peak in 1989, the average Bulgarian ate 79 kg of meat per year, while the Hungarian ate 116 kg and the Czech 100 kg. The average Frenchman ate around 100 kg per year at the same time.

GG: How did the years of communism impact food in Bulgaria, everything from making it to consuming it?

AS: Some products went out of favor. The list includes asparagus, artichokes, truffles, snails, olive oil, almonds, hazelnuts, and many European kinds of cheese produced by the already developing dairy industry. At the same time, other products were introduced, and they took over, refined sunflower oil is a good example here. Further to that, milk – fresh and sour – became a year-round product thanks to advances in industrial dairy technology.

Agriculture, meant to feed a growing urban population, was industrialized. But there’s a catch. Tomatoes and peppers, for example, were selected to improve the quantity and quality of the harvest, but this led to their range being reduced to a minimum. Old varieties were only retained in surviving private gardens. The same applies to most fruit and vegetables.

One thing is clear, and that is that during communism, Bulgaria quickly and radically lost its small commercial and artisanal industries; it failed to develop more sophisticated food products during that time. The production of luxury cheeses, wines, meats, and mixed vegetables – these fields of cookery missed out during four and a half decades of development. It seems that at least some of the existing artisanal knowledge and technology were also lost. Some alternatives emerged in the late 1970s and early 1980s when some factories began to develop lower-end market products, but they, too, fell victim to the problems of the socialist economy.

GG: And yet, other countries behind the Iron Curtain associated Bulgaria with nothing but the best produce and food.

AS: Bulgaria was no exception in that the communist regime severely curtailed the variety of products on the market. However, its tourism industry, which began to build an image through associations with sun, sea, and ripe vegetables, distinguished Bulgaria from some others, especially the northern communist countries. This made it a model of nutrition for some of them, such as Czechoslovakia.

GG: Did Bulgaria manage to preserve its pre-Communist food?

AS: The Bulgarian socialist state, especially after the 1970s, worked hard to codify a “national” cuisine. It was a state project that initially stemmed from the need to increase international tourism. It then became one of the pillars of social nationalism, the apotheosis of which was the celebration of the 1300th anniversary of the Bulgarian state in 1981.

All kinds of people were involved in this project: nutritionists, graduates of cooking schools, and people involved in the tourism industry. In their desire to present a ‘national’ cuisine to the world, these people organized various cooking competitions. Their aim was to gather recipes from the regions. The authenticity of these collections is questionable because many of the competitors had already passed through catering technical schools and were trained as chefs in state canteens.

Moreover, the first collection of socialist “national” recipes was an almost verbatim plagiarism from a book published in the 1930s. The problem is not only the failure to acknowledge the plagiarism, but that the source – Ana Hakanova’s cookbook “Bulgarian Folk Dishes” – is based on the recipes of three housewives from one family while claiming national representation.

But perhaps most importantly, all the efforts at creating a “national” cuisine have focused on the old countryside cuisine, completely ignoring the old city cuisine. To that point, the communist state framed Bulgarian national cuisine as ‘rural.’ This is not the case, for example, in Czechoslovakia, where urban recipes occupy a central place in describing local cuisine.

GG: How would you describe the Bulgarian food scene today? I’m sure you remember how in the 1990s, many Bulgarians couldn’t imagine their pizza or spaghetti without a hearty helping of ketchup. Is this period of confusion over?

AS: In my opinion, the most significant swing in recent years is the stratification of culinary tastes and practices in Bulgaria. The culinary trends of the Bulgarian people are not in unison like they were during socialism. [Then] there were, of course, some arrogant “red elites” who had privileged access to certain [unique] foods. But most of us had access to the same products, the same knowledge, and the same “patterns” of eating and cooking. That’s what has changed a lot.

People in Bulgaria have divided into more diverse groups. Differences in culture, financial means, and preferences produce much greater contrasts in menus. And to use your example of ketchup on spaghetti – I’m sure many still eat that. But there are also many others who not only recognize the excellent examples of pasta and pizza but know Italian cuisine well beyond that.

There are also huge differences in home cooking, expectations of restaurants, and travel behavior. It’s good when there’s room at the table for everyone, regardless of their tastes and abilities.